This list, #6 on our Top 10 Top 10, is kind of a free-for-all. I wouldn’t say it’s as vaguely defined as that last list, but it’s definitely more of a game game than trying to analyze who the most influential composers were. The idea is to pick composer whose overall output may not have been worthy of the greatest pantheon, but who did write one genre of music better than anyone else.

You’ll pick it up as you go along.

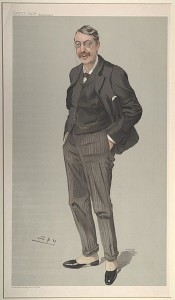

1. Johann Strauss Jr. (1825 – 1899) – Waltzes

Nothing beats a good old fashioned waltz. I use them in my own music all the time. And nobody ever wrote a better waltz than the great Viennese legend Johann Strauss, Jr. He was so passionate about three-quarter time that he even defied his famous composer father – in order to follow in his very footsteps (Johann Sr. had a banking career in mind for his sohn.)

Nothing beats a good old fashioned waltz. I use them in my own music all the time. And nobody ever wrote a better waltz than the great Viennese legend Johann Strauss, Jr. He was so passionate about three-quarter time that he even defied his famous composer father – in order to follow in his very footsteps (Johann Sr. had a banking career in mind for his sohn.)

He is rightly fêted every year on New Year’s Eve by the World’s Greatest Strauss Orchestra, the Vienna Philharmonic:

(Rosen aus dem Süden, VPO/Boskovsky)

2. Charlies Villiers Stanford (1852 – 1924) – English Church Music

Leave it to an Irishman to best the English at their own game. The English choral tradition is a quite specific thing. There’s the whole issue of dueling churches, the Anglican and the Catholic. Certain composers specialized in one or the other. Certain composers were glad to be denominational mercenaries.

Leave it to an Irishman to best the English at their own game. The English choral tradition is a quite specific thing. There’s the whole issue of dueling churches, the Anglican and the Catholic. Certain composers specialized in one or the other. Certain composers were glad to be denominational mercenaries.

Another irony in my selecting Mr. Stanford for this particular honor is that I submit as his outstanding work a Latin Motet:

(Beati Quorum Via, Cambridge/Rutters)

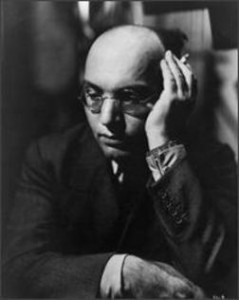

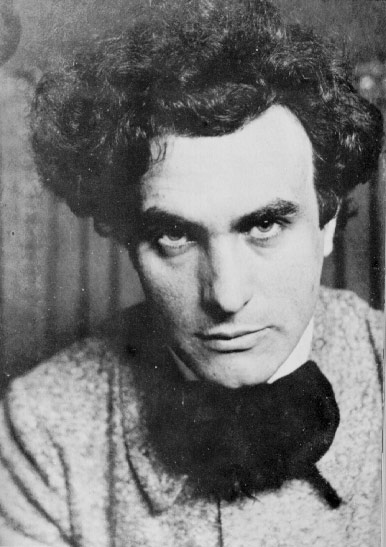

3. Kurt Weill (1900 – 1950) – Cabaret Songs

What I love about Weill’s songs is how sardonic they are. He displays a remarkably dark wit in the interplay of his spiky harmonies with the light lyrics (which he didn’t write). His music represents the gritty world that his characters inhabit.

What I love about Weill’s songs is how sardonic they are. He displays a remarkably dark wit in the interplay of his spiky harmonies with the light lyrics (which he didn’t write). His music represents the gritty world that his characters inhabit.

I also like how many of his cabaret songs are real Cabaret Songs – that is, the lyric sets them inside an actual cabaret. It’s much like a Saloon Song.

(“Alabama Song”, Marianne Faithfull)

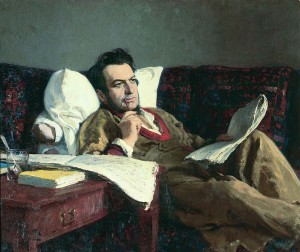

4. Giacomo Puccini (1858 – 1924) – Opera

Puccini appears on my lists of Top 10 Melodists and Top 10 Composers for Non Concert Settings (i.e. the stage). So, it should be pretty obvious why I would put him as the top opera man. I’ll be interested to see if the Wagner contingent mounts a strong defense. As much as I adore Richard’s music, I’d prefer to listen to it in smaller, concert-sized chunks.

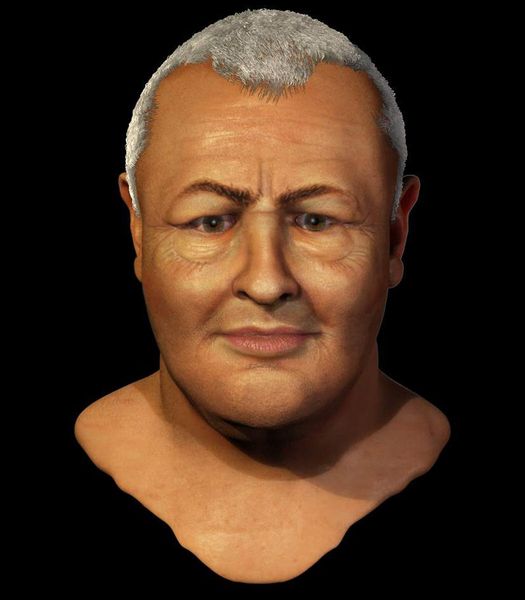

5. Vladislav Zolotaryov (1942 – 1975) – Bayan Music

OK, so here’s a composer and an instrument that you’ve likely never heard of, but get ready, because it’s going to be way better than you expected.

First off, this is a bayan:

Basically, it’s a Russian/Eastern European accordion, which differs from the regular accordion in some way or another.

[Now, apparently there is an alternate meaning to the word ‘bayan’ of which I’m wholly unaware. If you want to find out what it is, or what it might be, or what ‘bayan’ might autocorrect to in some bizarre google conspiracy world, you could do a google image search for ‘bayan’, but I strongly recommend against it.]

So, we’ve established that much. Everything I know about this composer’s biography comes from the liner notes of the one CD I’ve found with his music on it. Apparently his parents were prisoners of the Gulag and he was born in the northernmost region of northeastern Siberia. Great start. He excelled at the bayan, and got some training in music at a small conservatory. He was rejected several times from the Moscow Conservatory before he finally made it in to study composition. He committed suicide at the age of 33.

He composed a number of pieces for other instruments, but this is where he made his mark:

(“I’m recalling instances of gloomy sorrow”, David Farmer)

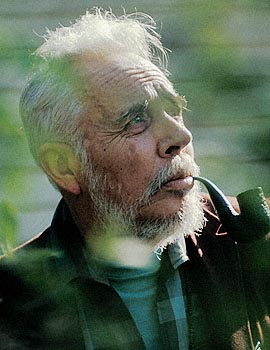

6. (F.) Joseph Haydn (1732 – 1809) – Minuets

In many ways, I think the minuet was Haydn’s genre par excellence. These pieces were not written for dancing. They were written to add a dance scene into the dramatic flow of his symphonies (as I touched on in the discussion of Piazzolla in last list.) Haydn was a wry observer of human interaction, and he humanizes his noble acquaintances in these minuets.

We might hear the heavy brocade weighing down the upper crust, or see the lush curtains and the warm glow of the gaslit ballroom. We might sense the hesitations and embarrassments of the youth present, relishing their only opportunity for flirtation in a highly formalized milieu (then we catch them as they sneak out to the veranda.) There are the dancers who don’t quite know the steps and their bashful apologies; then there are the big fat ladies with two left feet who couldn’t be less aware.

It’s all just so funny and charming and gemütlich:

7. Sufjan Stevens (1975 – ) – Pensive Old-Testament Banjo Ballads

OK, so there’s obviously a lot of things that Sufjan Stevens does impressively well. And in my opinion, there’s a lot of things he does better than anyone else. But in this category, he’s pretty much got to be the undisputed leader, right?

8. J. S. Bach (1685 – 1750) – Music for Solo Strings

I think Bach’s cello suites and solo violin sonatas & partitas are every bit as great an accomplishment as his works for organ and the big choral-orchestral combinations. Not only are they shockingly original and deeply emotive, but they link him to other European masters of the solo viol, like Marin Marais and the incorrigible Monsieur de Sainte-Colombe.

9. W. A. Mozart (1754 – 1792) – Piano Concerti

This is a genre-composer combination on many levels: that is to say, not only do I think Mozart wrote the definitive collection of piano concerti, but I think that the piano concerto was the definitive Mozart genre. So chew on that one for a while.

For me, these are Mozart’s greatest operas. They have the beauty, the drama, and the songfulness of his operas, but they condense the plot into about 30 minutes. Who wouldn’t like that?

(D minor concerto, Brendel, St. Martin/Marriner)

10. Michel LeGrand (1932 – ) – Jazz Opera Film

Aside from Les Parapluies de Cherbourg, just how many other Jazz Opera Films are there? Well, there’s a least one: Les Demoiselles de Rochefort – ALSO by Michel LeGrand. I’d say he sweeps this category.

Aside from Les Parapluies de Cherbourg, just how many other Jazz Opera Films are there? Well, there’s a least one: Les Demoiselles de Rochefort – ALSO by Michel LeGrand. I’d say he sweeps this category.

No but seriously, he wrote such a gorgeous score for Les Parapluies. And I know there’s a lotta h8trs out there, and h8trs gotta h8t. And I hate that Steven Sondheim is one of them, and that he said that he thinks this “just doesn’t work” or whatever. But then again, he was in Camp which might be the worst movie ever made, so with all due respect Steve, let’s just tone it down an notch, shall we?

I mean, come on:

Discuss

This is easily the most ridiculous list so far. [Just you wait!] But I think it should make for a good game, because there’s at least three ways to play:

1) Make your own damn list

2) Replace the composer for the category.

Example: Khatchaturian was a way better writer of waltzes than Johann Strauss Jr. ever was! [as if]

or Thomas Tomkins was a much finer composer of English choral music than was Charles Villiers Stanford! [perhaps…]

3) Drop one of my category-composer combos and say that your guy did his thing better than mine did his.

Example: Conlon Nancarrow was a much better writer of boogie-woogie piano rolls than Kurt Weill was of Cabaret Songs!

If you read David Hajdu’s Strayhorn biography

If you read David Hajdu’s Strayhorn biography  I’m not sure why, but I somehow feel like Steve Reich is a better minimalist than a composer. It’s probably silly to even talk about such things, but I’d be interested in hearing if anyone else knows where I’m coming from.

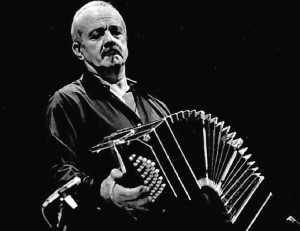

I’m not sure why, but I somehow feel like Steve Reich is a better minimalist than a composer. It’s probably silly to even talk about such things, but I’d be interested in hearing if anyone else knows where I’m coming from. The great innovator of the Argentinian Tango, Ãstor Piazzolla studied composition with the mythical French pedagogue

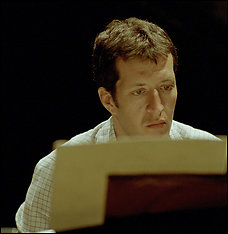

The great innovator of the Argentinian Tango, Ãstor Piazzolla studied composition with the mythical French pedagogue  Thomas Adès is the real deal: a composer who writes music that is both interesting and emotional, has the piano chops to back up his incredibly demanding instrumental ideas, and makes a living off writing and presenting his own works.

Thomas Adès is the real deal: a composer who writes music that is both interesting and emotional, has the piano chops to back up his incredibly demanding instrumental ideas, and makes a living off writing and presenting his own works. Messiaen reminds me of two other composers on this list: Arvo Pärt, because of his fervent and mystical religious beliefs; and Ligeti because of their shared experience as prisoners during WWII (Ligeti had it much harder) and because they both wrote music that explores new ground while maintaining a direct connection to the romantic tradition (Messiaen’s is stronger).

Messiaen reminds me of two other composers on this list: Arvo Pärt, because of his fervent and mystical religious beliefs; and Ligeti because of their shared experience as prisoners during WWII (Ligeti had it much harder) and because they both wrote music that explores new ground while maintaining a direct connection to the romantic tradition (Messiaen’s is stronger).

Isn’t that kind of an embarrassing trove of ‘firsts’ for a man who’s been reviewing theater for like 20 years or something? Critic as fan v. critic as practitioner… I’d better stop before this whole thing turns into a post about Pauline Kael.]

Isn’t that kind of an embarrassing trove of ‘firsts’ for a man who’s been reviewing theater for like 20 years or something? Critic as fan v. critic as practitioner… I’d better stop before this whole thing turns into a post about Pauline Kael.]