For a breezier take on this topic, I posted a vlog on the very same subject.

In certain musical circles, you hear a lot about composers/film productions/record companies heading to the Czech Republic and Ukraine to make orchestral recordings on the cheap. In need of a new round of orchestral recordings of my own compositions, I decided to get in on the action.

It took but a single google search to point me towards czechrecordings.com. This a business run by an Englishman named Mikel Toms who manages recording projects for three orchestras in the CR: the Czech Philharmonic, the Brno Philharmonic, and the Janacek Philharmonic in Ostrava.

I first approached Mikel about booking a recording session in May, and he recommended the least expensive option to me, the Janacek Philharmonic Ostrava. This band may come cheap, but don’t be fooled – it’s a real live professional orchestra with a fine pedigree and an excellent history. They’ve even recorded the complete works of LeoÅ¡ JanaÄek, and trust me, that ain’t easy. His music is weird and hard and they play it well:

(excerpt from The Fiddler’s Child performed by the Janacek Philharmonic Ostrava)

Five months elapsed between the time I first asked for a quote and the session itself. I’m told it’s relatively easy to book a single session with only a few months’ notice, but for more extensive projects these orchestras book about 18 months out. During the early days of planning, it sometimes took a little prodding to get a response out of Mikel, but as the date approached he was very attentive; he put me in touch with the recording engineer, arranged for the orchestra’s driver to take me to the hall, and called to check in on me at my hotel.

Now to brass tacks: how much did it cost and was it worth the price?

I employed an 86 person orchestra in Ostrava – so, like, a real, big symphony orchestra. The single three-hour session cost roughly $6,000, including all personnel, library, and recording costs, and it was a complete buyout, i.e. the orchestra gets no back end on the deal, and I am totally free to use the recordings as I like.

I got a surprisingly good deal on my round trip from the U.S. to Europe ($700). I travelled from Prague to Ostrava by train ($15 round trip) and stayed at the best hotel in town for two nights (about $150 total.) So the complete project came in just under $7K (not including editing, mixing, and mastering, which I did in the US with my collaborator Jon Brennan.)

Before I signed the contract to work with the JPO, I investigated the possibility of recording in the US, but professional orchestras here aren’t really “for hire” in the way that these Czech orchestras are (they certainly don’t have web sites advertising their availability.) There are, of course, studio orchestras around, and outside the big ones in LA, the studio orchestras in Nashville and Seattle are most prominent. Both quoted me $21,000 for the same project.

One third the price seems like a pretty good deal to me. But was it worth it, or did I really get a two-thirds inferior product?

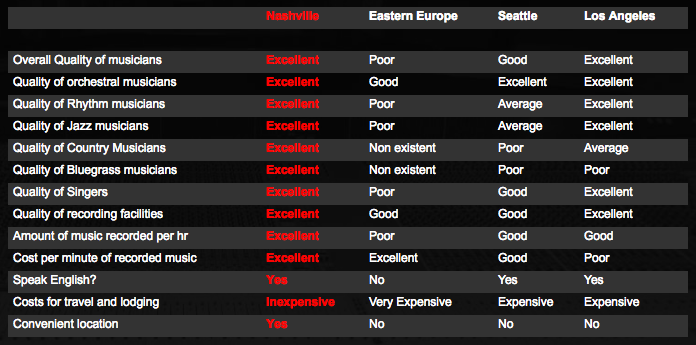

Conveniently, Nashville Music Scoring’s web site offers a (very slanted) chart comparing their services to those in other cities:

They also have dedicated comparison pages where they talk a big game and belittle the services offered by their competitors:Â “We understand how to play all styles of music. Do you really want to record Bluegrass in Prague, Big Band in Bratislava or Jazz in Sofia?”

Well, perhaps not, maybe I don’t really want to record classical music in Nashville either? My understanding is that these studios are set up for film style recording anyway, i.e. they record strings and winds/brass/percussion separately. In Ostrava I was able to work with the whole orchestra in one place – you know, like an orchestra.

[A side note: Nashville claims that Eastern Europeans’ ability to record Country/Western music is ‘non-existent’. One of the things I learned during my several months’ immersion into Czech culture is that country and bluegrass are hugely popular there to the point where you even see people driving around with Confederate flags on their cars.]

NMS also mentions that they are able to record much more music in a shorter amount of time. I budgeted rather conservatively in this regard, and I just about nailed it: I recorded about 18 minutes of music in one three hour session. From what I’ve heard, that beats the L.A. industry standard of 15 minutes/session.

It’s true though that the orchestra was a little spotty as far as English was concerned. I anticipated this and I took private Czech lessons for two months prior to my trip ($25/hr). This gave me enough Czech to introduce myself, address the players by the names of their instruments, announce rehearsal letters and measure numbers, and give a few other simple instructions. I would say I spoke about 1/3 Czech, 1/3 Italian, and 1/3 English. Of course, one tries to speak as little as possible in these situations anyway. (Leonard Slatkin once told me that if you really want to learn how to conduct, go to a country where you don’t speak the language at all and see what you can accomplish.)

Enough people spoke English that I was also able to get across more detailed instructions with the help of their translations. Here I must single out the efforts of the producer, Jan KoÅ¡uliÄ. Not only did he translate, but he was also just an excellent all-around producer/engineer. His equipment was top notch and he even kept detailed notes on the scores about what we got on which takes.

Final review: if you want to record classical music with a full symphony orchestra, I can not imagine a better deal than working in the Czech Republic, and with the Janacek Philharmonic in particular. I feel as though I got the best possible value available for a project like this and I would recommend the experience unequivocally to my fellow composers.

And what did the recordings sound like? Stay tuned…