It’s not so often that Cincinnati, OH feels like the center of the musical world, and it’s even rarer that I get to work with several of my musical idols on a single project. But every once in a while, the stars align, and this past week was one of those rare occasions.

March 30 & 31 saw the world premiere of Philip Glass’s new cello concerto (no. 2) by our CSO. I’ve never thought of myself as a big Philip Glass fan, but in preparing for the concert this past week I had occasion to go back through my CD collection, and there’s no denying that I’ve had my Glassy phases. When I was a freshman in college, I used to listen to the last movement of his second symphony over and over again on repeat (and yes, I realize that many of my readers will find that concept delightfully ironic.) The coda is SO MUCH FUN and it features my favorite repeat in all of Glass’s work, because just when you think the movement is about to finish, he goes back in for another round (1:03):

I’ve also harbored attachments to the first violin concerto and “Glassworks” among others, which, when I added it all up, made me realize that I really am a Philip Glass fan. Which I think is one of those things that serious musicians aren’t supposed to say, but all the more reason for saying it.

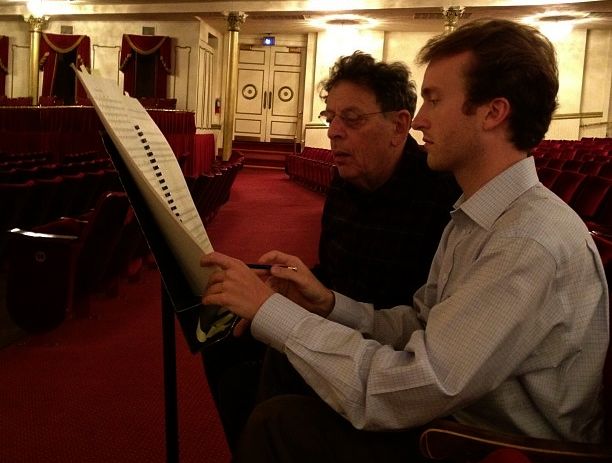

And all the more reason why this week gave me such a buzz. The experience was only amplified by the fact that Philip is a gregarious and charming human being. A big part of my job this week was to interview him publicly, and let me tell you, that guy’s a talker. If Charlie ever had him on the broadcast, he wouldn’t be able to get in a word edgewise (which, perhaps, is why Mr. Glass has never appeared.)

I’ll admit that I was a little put off when I first received the score to the concerto about a month ago, and I found out that the music for his new piece was not actually new — it turns out that the concerto is a condensation of his score for Naqoyqatsi, the third installation of Glass and Godfrey Reggio’s Qatsi Trilogy. But the thing is, everyone involved treated it like it was a brand new piece of music, and because of that, it became a new piece of music.

Much of that had to do with the collaborators involved, Matt Haimovitz and Dennis Russell Davies. Now, when I said at the top of this post that I got to work with ‘several of my musical idols,’ DRD was definitely included in that mix. My obsession with him also dates back to my first year of college, when my eyes were opened to the greater world of new music, and I eagerly began buying up recordings of Schnittke, Pärt, and Glass among others. So many of the albums featured Dennis Russell Davies as conductor that his became a household name in the house of my brain.

First off, I’m happy to report that he’s another class act, all the way. Secondly, he fucking recorded Alfred Schnittke’s 9th Symphony, which, on a spiritual level, places him ad dexteram Patris as far as I’m concerned. And this is in addition to the most baddass recording of the Viola Concerto and one of the single greatest albums of all time, Marianne Faithfull’s rendition of The Seven Deadly Sins. Not to mention the complete Haydn Symphonies, which, correct me if I’m wrong, is only the third such survey ever recorded??

Ahh, just thinking about these people gets me all in a tizzy, but I want to emphasize that the best part is that they were all really dedicated to this project (especially Matt Haimovitz who became one of my musical idols after working with him), they all contributed ideas that made it work, and, what made it so fulfilling on a personal level, they actually listened to and incorporated my ideas — little old me, the assistant conductor. That’s a rarity for artists who don’t even approach these guys’ stature, and it was an honor to contribute what little I did.

But wait, there’s more!

Because when I said that earlier that Cincinnati felt like the center of the music world this past week, it wasn’t just because I got to hang out with famous people. The seventh annual MusicNOW Festival took place, organized by Cincinnati native Bryce Dessner. He collected, among others, the following musical entities: eighth blackbird, Nico Muhly, James McVinnie, Sam Amidon, and no less a deity than Sufjan Stevens.

Sufjan was premiering a new song cycle co-composed with Nico Muhly and Bryce Dessner himself. The one bummer of my week is that I couldn’t get over to hear this collaboration (since I had to be next door attending to the recording of the Glass concerto).

Thank god for YouTube bootlegs!

Nothing beats a good old fashioned waltz. I use them in my

Nothing beats a good old fashioned waltz. I use them in my  Leave it to an Irishman to best the English at their own game. The English choral tradition is a quite specific thing. There’s the whole issue of dueling churches, the Anglican and the Catholic. Certain composers specialized in one or the other. Certain composers were glad to be denominational mercenaries.

Leave it to an Irishman to best the English at their own game. The English choral tradition is a quite specific thing. There’s the whole issue of dueling churches, the Anglican and the Catholic. Certain composers specialized in one or the other. Certain composers were glad to be denominational mercenaries. What I love about Weill’s songs is how sardonic they are. He displays a remarkably dark wit in the interplay of his spiky harmonies with the light lyrics (which he didn’t write). His music represents the gritty world that his characters inhabit.

What I love about Weill’s songs is how sardonic they are. He displays a remarkably dark wit in the interplay of his spiky harmonies with the light lyrics (which he didn’t write). His music represents the gritty world that his characters inhabit.

Aside from

Aside from