Readers of my blog will know that I was just in Chicago this past weekend giving talks for the CSO’s Rachmaninoff/Shostakovich concerts. What they won’t know, unless they actually attended the concerts themselves, and what I am committed to exposing right now, is that the soloist, one “Kirill Gerstein“, showed up wearing the least appropriate attire possible. See below:

Do you see That, what he is wearing in that photo? Yes that, THAT exact outfit (OK fine, plus a black suit jacket) is exactly what he wore to play a concerto with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. No tie, no tails, just all black, open-collar. Many of Mr. Gerstein’s bios mention that he has extensive experience in jazz as well as classical music. Well, if that be true, he should sure as hell be able to tell the difference between a cocktail lounge and the stage of Orchestra Hall!

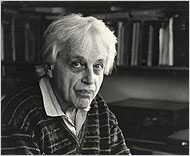

I’ve ranted about men’s fashion in the classical music industry many times before, and certainly Mr. Gerstein is not the only offender. Mr. Gerstein is merely representative of a larger problem, namely that soloists and conductors seem to think that their individuality stems from their wardrobe rather than their musicianship. And maybe with some of these artists, that is the case. But look at our great forbears in the field:

Mssrs. Heifetz, Rubinstein and Giulini were all perfectly content to dress in uniform. And would we say that these gentlemen were lacking in individual style? Quite to the contrary! They each exuded style and grace and they were positively dripping with musicality. And yet, like other great performers of yesteryear, these men were perfectly content to make their public statements with their music rather than with their wardrobe.

When conductors and soloists do dress in uniform with the orchestra, it sends an important message to the members of the ensemble: we’re in this together. It shows the orchestra members that you are not so arrogant that you must have some vulgar costume to draw attention towards yourself – rather, you are prepared for the exalted business of making music. You are willing to abide by the same code as the rest of the musicians in front of you in order to share in this experience.

And to the Charlie Roses of the world: looking purposefully unkempt (i.e. CR’s infamous un-buttoned/cuff-linked shirt sleeves) takes just as much effort as looking presentable. We’re on to you.

Men of the musical world: glam it up! GLAM IT UP!!!

Mr. Gerstein: on behalf of ticket-holders everywhere, when we pay upwards of $100 both to hear and to see you perform, we expect you to look presentable. Put on a tie for goodness’ sake.

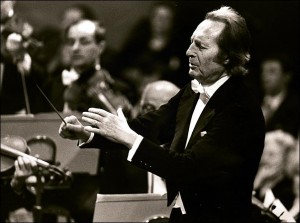

Now that the basics have been established, one may consider certain variations and exceptions. Â Many conductors use variations in their wardrobe to present an individualized podium presence. Â The so-called “Nehru” jacket is a form of attire worn by a great many conductors to show how individual they are. Â This can be appropriately worn with an orchestra wearing either White or Black Tie, but not suits.

Now that the basics have been established, one may consider certain variations and exceptions. Â Many conductors use variations in their wardrobe to present an individualized podium presence. Â The so-called “Nehru” jacket is a form of attire worn by a great many conductors to show how individual they are. Â This can be appropriately worn with an orchestra wearing either White or Black Tie, but not suits. This is a dress frequently worn by Mr. Slatkin and historically associated with various mafioso types. Â A sort of “inverted Black Tie”, this outfit defies easy categorization. Â It has a solemn, yet bold overall appearance, and combines the class of a tuxedo with the “attitude” of all black.

This is a dress frequently worn by Mr. Slatkin and historically associated with various mafioso types. Â A sort of “inverted Black Tie”, this outfit defies easy categorization. Â It has a solemn, yet bold overall appearance, and combines the class of a tuxedo with the “attitude” of all black.