I recently had a request from a young composer to vlog my composition process as I was writing a piece of music. I declined, for a number of reasons.

Yearly Archives: 2017

The Lighter Classics

One thing sorely missing from the concert life of major symphony orchestras these days is the Light Classical repertoire. The major conductors (and those hoping to replace them)Â seem to think that by associating themselves with Serious Masterpieces written by Intense Male Composers (Mahler and Shostakovich) they too will go down in history for their Deep Interpretations.

It’s a pity of course, because the lighter works add sparkle and luster to any program. They often carry strong thematic connotations, frequently stemming from ballets and operas, or representing various folk traditions. They can add context to more serious works (all the major composers in Europe, for example, adored the work of Johann Strauss II) and generally leaven a program that might be overly dense.

Suites, medleys, and other short works also allow for variation from the standard overture-concerto-symphony format. O-C-S is a fine concert format, but it’s even more effective when it’s not all you hear.

All this is why I was so very pleased when I stumbled upon David Ewen’s The Lighter Classics in Music, a beautifully written survey of this particular repertoire published in 1961 (basically on the eve of this music’s ubiquity.)

This book introduced me to many hidden gems, by composers well-known, lesser-known, and unknown (to me anyway), much of it music that hasn’t made it through the filter of history. Ewen writes beautifully about these composers and their music, and he does a fine job of representing the geographic spectrum of this particular style. I’d very much recommend picking up a copy, but if you don’t care to, I’ve assembled a Spotify playlist (above) of representative works from all the composers mentioned in his book.

One thing worth noting is that this stuff didn’t just die off in 1961: composers are still writing light music. We just have to listen.

Schubert’s 10th

On a recent program, the local symphony orchestra included a movement from the reconstructed “10th” symphony by Franz Schubert, as realized by Peter Gülke. It is an abomination at every level, and it is a scandal that Schubert’s name should be associated with this musical misadventure.

The music sounds nothing like Schubert. It sounds more like Vaughan Williams. Rather, it sounds like a high school composer’s bad imitation of Vaughan Williams. Actually, that’s not being fair to Vaughan Williams. Or high school composers. Or bad imitations.

Gülke wasn’t the only one to realize Schubert’s sketches for a late symphony in D Major; Brian Newbould also created a version, and that version was later revised by a certain Pierre Bartholomée. But the materials they were working from were fragmentary at best, mostly just a few melodic ideas with some bass lines filled in and the occasional working out of inner voices.

No surprise then that neither the harmonies, melodies, nor orchestration make any sense in the version I heard. The big lesson here is just how many iterations a piece – nay, a phrase, a motive, even a note – undergo on their way to becoming a completed work that’s representative of a composer’s style. Many composers have tried to hide the painstaking process behind their greatest works (see, for example, Johannes Brahms, who burned all his drafts) but even a Mozart doesn’t necessarily sound like Mozart at the first stages of a draft. Certainly a Gülke doesn’t sound like a Schubert.

But on top of that, there’s another, much more objective sense in which this piece can not be said to be Schubert’s 10th symphony: Schubert only wrote seven and a half symphonies in the first place.

You probably get what I mean by the ‘and a half part’ – the two movements that comprise Schubert’s ‘Unfinished’ Symphony. But, you protest, the ‘Unfinished’ is Schubert’s 8th, and the 9th is the well-known C Major symphony, so certainly he composed eight and a half symphonies at the very least.

If that be the case, ask yourself this: when’s the last time you heard Schubert’s 7th? Not ringing any bells? That’s because there is no such piece! Rather, one might say that any piece purporting to be Schubert’s 7th suffers from the same essential musical invalidity as does the so-called 10th: the piece only exists in sketches which have since been realized (also by Newbould.)

Actually it’s a little more complicated. When publishers were bringing out Schubert’s symphonies, they purposefully left the No. 7 spot blank, publishing the ‘Unfinished’ as No. 8 and the Great C Major as No. 9. Scholars had come across references to a symphony composed by Schubert that they believed to be lost (the so-called ‘Gastein Symphony’). They kept a spot open in the chronological numbering in the hopes of finding it.

It’s now generally agreed that the symphony referred to was in fact the Great C Major. Which, ironically, means that the musicologists did the right thing, since the Great C Major really should be Symphony No. 7 (if we’re only counting completed symphonies.)

To tidy up the rest of the mess, I’d propose (to… the world?) that the ‘Unfinished Symphony’ should just go by that description alone – no number at all.

But at the very least, if you’re going to keep performing this so-called 10th symphony (and by all means, please don’t) at least put Gülke’s name up front and bury Schubert’s deep in the program notes; it’s the least we can do.

Halloween Belongs to Alfred Schnittke

Did anyone even celebrate Halloween in the Soviet Union? They did not. But does my boy Alldead Slitsya need some bogus holiday to creep you tf out? HE DOES NOT.

This number,”Es geschah…” from the opera Historia von D. Johann Faustus, is so satanic – and I’m guessing you didn’t know this already – that it was used by Alexander Plato in the final round of the 2016 Armenian Eurovision Song Contest Finals:

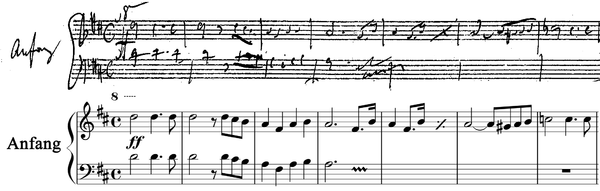

Trio for Viola, Horn, and Piano

This piece was composed for two very good friends, Andy and Mary Moran, whom I first met in the summer of 2005 at the Pierre Monteux School. Andy was attending as a conductor and horn player, Mary as a member of the viola section, which meant I got to sit next to her in orchestra all summer, which I count among the singular delights I’ve been afforded.

Andy is now Professor of Horn and Orchestral Director at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point; Mary is a musician and staff member with the Central Wisconsin Symphony. The premiere was given at the UWSP School of Music, by Mary and Andy and Janna Ernst on the piano. Shortly thereafter, I travelled to Wisconsin to give further performances (as pianist) both there and in Chicago, and we have since performed it at additional concerts as part of the ARTi Gras Festival in Central Wisconsin.