Hi blogfanz – I’m back, and I’m glad to be returning to our top 10 top 10 with List #8, the Top 10 BEST Composers, where by “BEST” we mean something along the lines of “Most Technically Accomplished”.

“Compositional technique” is a phrase that gets bandied around a lot (among a tiny, tiny élite of classical musicians and critics). But I don’t think I’ve ever heard it defined. Composers confront a series of Design Challenges and Execution Challenges as they write a piece. So, is a composer’s technique simply a question of how well he or she executes a given design? Is it possible to separate the design from the execution?

My favorite example of this conundrum is Gordon Jenkins, a composer/arranger from the Golden Era of pop music who wrote beautiful, lush arrangements for Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, Judy Garland, et al. As a composer, he specialized in writing “concept albums” for many of these collaborators.

His concepts for these albums were, in a word, ludicrous – Frank Sinatra taking a guided tour of outer space, for example. But the music he wrote to accompany his zany scenarios is gorgeous. It’s like, “yeah, if Frank Sinatra took a space ship to Saturn and then sang a jig about it, this is the best possible version of that jig.” You know?

Here’s what I came up with. We’ll talk more about the criteria at the end:

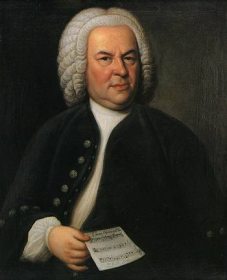

1. J. S. Bach (1685 – 1750)

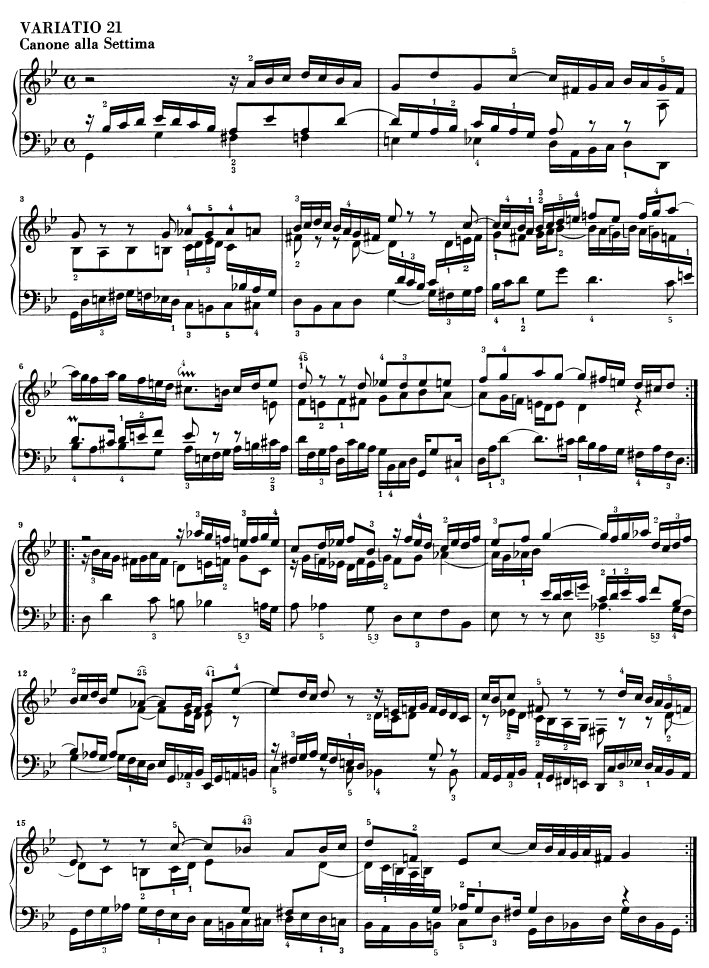

Any person who writes a canon at the 7th, smoothly and gloriously, you do not mess with this person.

(Goldberg Variation 21, Glenn Gould ’54)

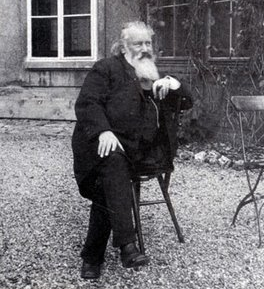

2. Johannes Brahms (1833 – 1897)

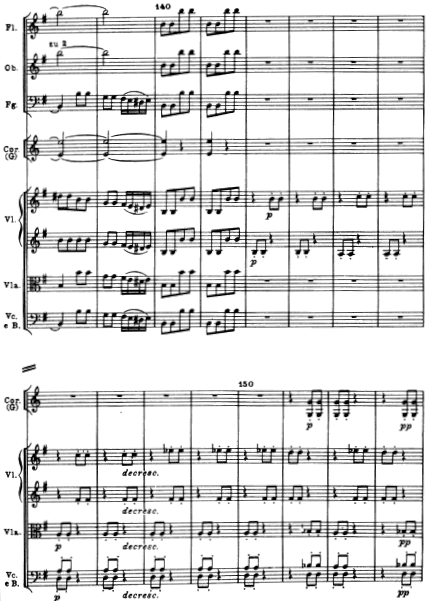

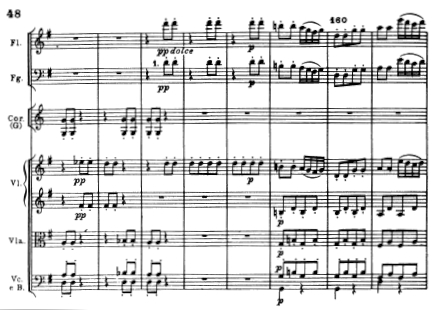

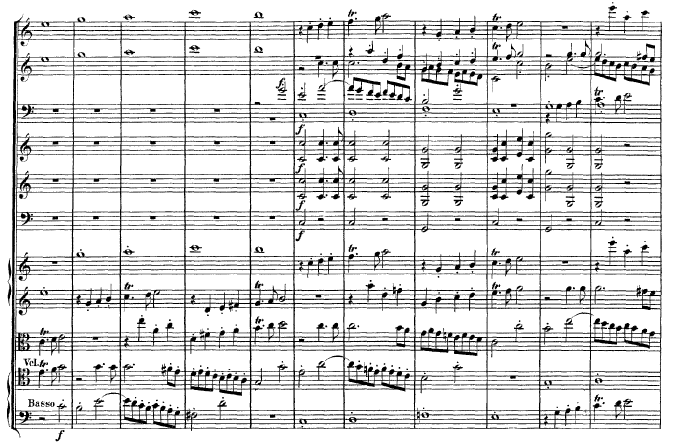

Here’s some mad compositional technique: Brahms’ Symphony No. 2, second movement, letter D. This audio begins 4 bars before the printed excerpt. Here’s what happens:

00:00Â Impassioned 2-part counterpoint; violins v. lower strings; build-up to

00:11Â The previous two lines are remixed into one, and this composite line is pitted against itself; build-up to

00:21 Dramatic tremolo in strings, winds play the main motive (ascending 3-notes), trombones recall the main motive from the previous movement of the symphony.

00:32 Letter D:

Violins and bassoon play the counterpoint from the beginning of this movement, flute and oboe keep playing the motive from the last section, long tones in the lower strings build drama and tension into

00:48Â Parallel section to 00:21

This is what we call ‘tightly constructed’ – the themes all relate to each other, play against each other, appear and reappear, and build up into a large scale structure. But honestly, you don’t have to appreciate ANY of this to enjoy the symphony. This wealth of composerly technique is in the service of beautiful, dramatic, and emotional musical story-telling.

3. Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827)

I say we let Lenny sort us out on this one:

4. (F.) Joseph Haydn (1732 – 1809)

Now, a lot of the tricks that Lenny was just talking about w/r/t Beethoven, I’m convinced Beethoven learned from Haydn. That is to say – the guy (Haydn) was killer when it came to form. But he (Haydn) also happened to be really good at all the things Lenny claims Beethoven sucked at: melody, harmony, fugues, etc. Haydn dazzles us, leaves us spinning, and has a ball doing it.

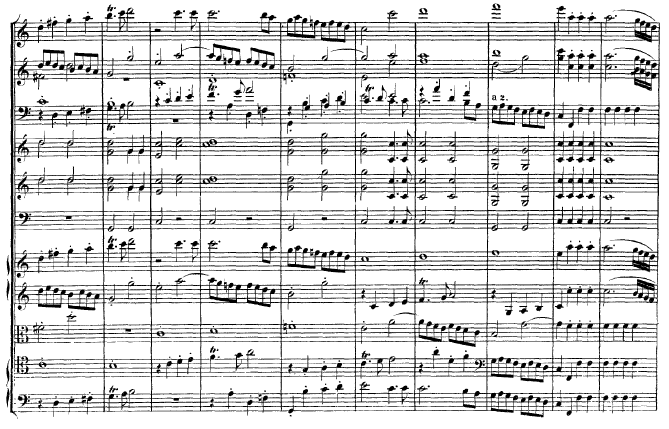

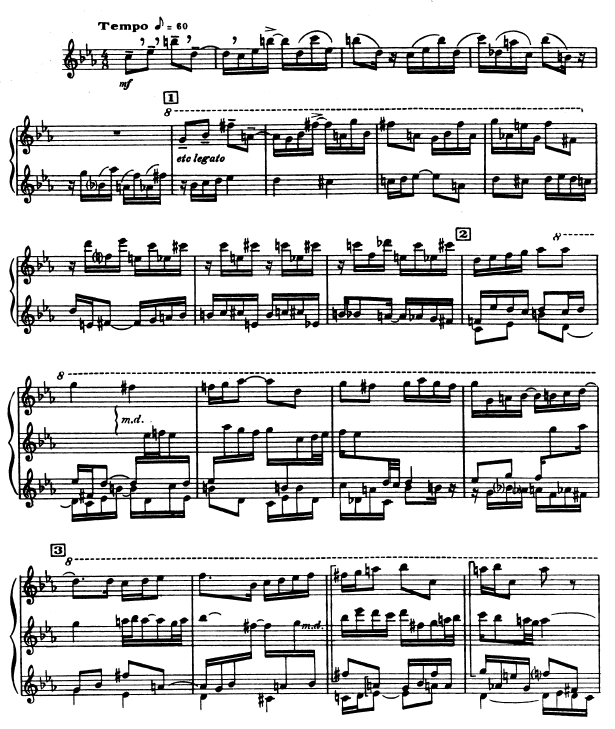

So for all his fancy tricks, I’m going to present a passage that seems rather mundane – just 8th notes, in pairs. The trick though, is that he slowly modulates the harmony, dynamics, and instrumentation to bring us back to the opening theme of this, the last movement of his 88th Symphony:

(score picks up on 00:04)

It’s like you’re driving around some back country roads, and just when you think you’re totally lost, you look up and it turns out you’re back where you started. That’s Haydn.

5. Johannes Ockeghem (1420ish – 1497)

I’m hardly an expert on this composer or his music. But like many an undergraduate music major before and since, I did at one time learn about the staggering contrapuntal accomplishments of Flanders’ greatest son.

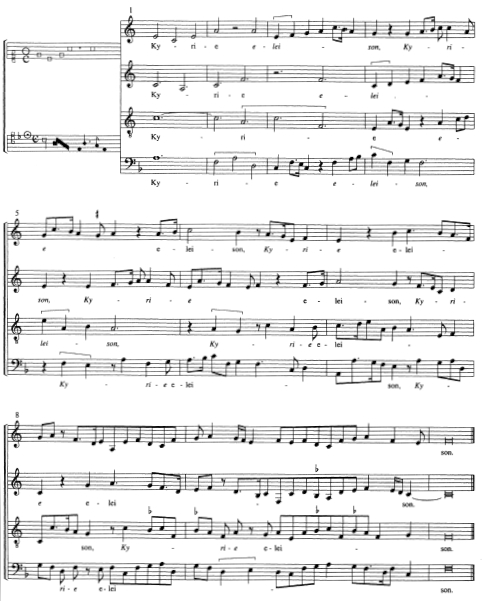

Let’s look at his most famous work, the Missa Prolationum, so called because of its extensive use of “prolation canons”. It works like this: you all know what a canon is – “Row, row, row yr boat”, “Frère Jacques”, etc., anything where one guy sings a tune and the other guy starts singing the same tune a little later and it all works out harmonically. Well, in a “prolation canon” (which is more commonly known as a “mensuration canon”), the two guys sing the same tune at different speeds. Normally, they have a relation to each other – like twice as fast or twice as slow.

They don’t always have to stagger their entrances either – they can both start singing at the same time and it still counts. Ockeghem took this idea of mensuration canons to the extreme. Here’s the Kyrie II from his mass. There are two melodies: one in the soprano and alto, and another one in the tenor and bass. The soprano and alto sing their melody at different speeds. The tenor and bass sing their melody at two entirely different speeds. What’s more, the two melodies are very closely related.

You try to do that.

6. Claude Debussy (1862 – 1918)

I’ll turn over the floor again, this time to Esa-Pekka Salonen:

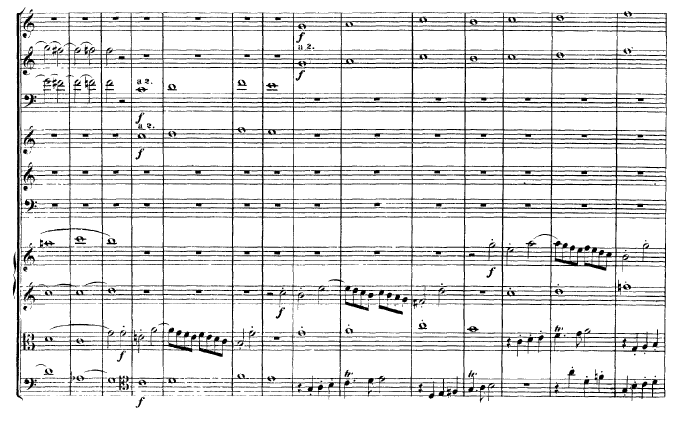

7. Wolfgang Amad̩ Mozart (1754 Р1792)

I don’t know where to even begin talking about Mozart’s ridiculous compositional technique, but you can’t do much worse than the final set of canons in his last symphony, No. 41 (the “Jupiter”). This piece is chock full of canons, fugues, and other contrapuntal devices – and yet, you never get tired of them (unlike, let’s admit it, Bach). It’s just one vivacious bar after another:

8. Gy̦rgy Ligeti (1923 Р2006)

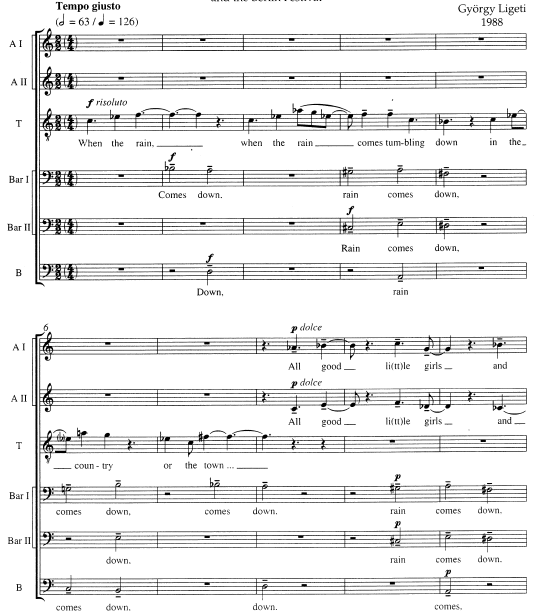

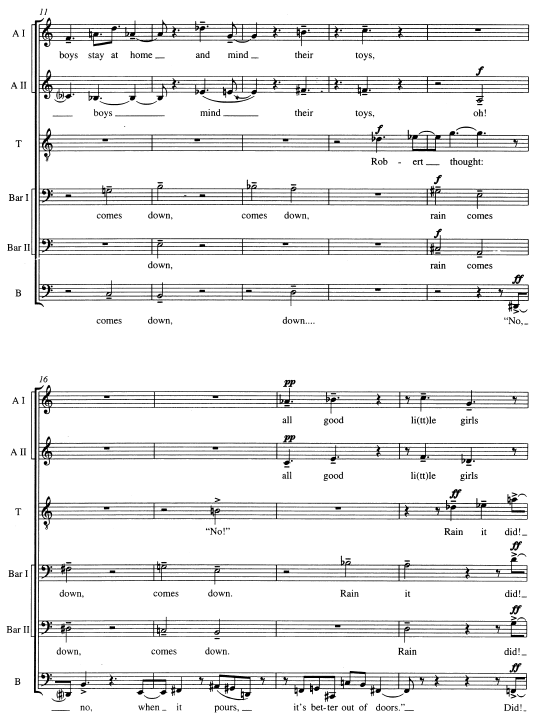

With a mind to the generalish audience that sometimes reads this blog (if anyone’s actually made it this far), let’s turn again to the Hungarian composer’s Nonsense Madrigals, based on texts by Lewis Carrol.

Here’s “Flying Robert”:

So what makes this so great? Well, first off, let’s figure out what’s going on.

Element the first: The tenor has a melody (“when the rain… when the rain comes tumbling down… in the country or the town”). Each of the three phrases of the melody begins the same and builds to a higher note. The rhythm of the melody is irregular – it has a rhapsodic quality.

Element the second: This piece is a passacaglia, which means there is a repeated, regular figure in the bass line. Ligeti does that and also includes the two baritones in establishing the pattern. So even though this pattern gets shifted from beat to beat, there is a regular pulse going on, grounding the music.

Element the third: When the altos come in, they pick up the tenor’s melody, but their rhythm mimics the regular pulse of the passacaglia people, but shortening their pulse by 1/4 of the value. Just to make things a little more complicated, at the top of the third system, the second alto starts drifting off into his own little world.

So again, what’s so great about this? It’s that Ligeti combines the elements in a way that gives the listener a simultaneous sense of regularity and irregularity – everything sounds natural but odd, logical but unpredictable. It works like a precision machine, as does much of his music, including the wild, 100-instrument scores from his early period.

9. Igor Stravinsky (1882 – 1971)

I’ll admit, there’s occasionally things that are clumsy in Stravinsky’s writing – some of his meter and barring choices can be rather confusing at times – but the flaws are very minor, and easily overlooked when taken in context of his overall skills as a writer of music.

Since fugues seem to be a common theme of this list, here’s a great one:

10. Alban Berg (1885 – 1935)

Alban Berg, the shining light of the Second Viennese School, has gotten all too little love up in these lists so far. Finally, we’ve arrived at his category.

Alban Berg, the shining light of the Second Viennese School, has gotten all too little love up in these lists so far. Finally, we’ve arrived at his category.

What I personally find so impressive about Berg’s writing is his ability to unite disparate elements. He chose to use a wide range of compositional tools: tonality, atonality, dodecaphony. He wrote waltzes and polkas, but infused them with eerie harmonies. He wrote startling, arhythmic sound masses and contrasted them with delicate, crystalline chords.

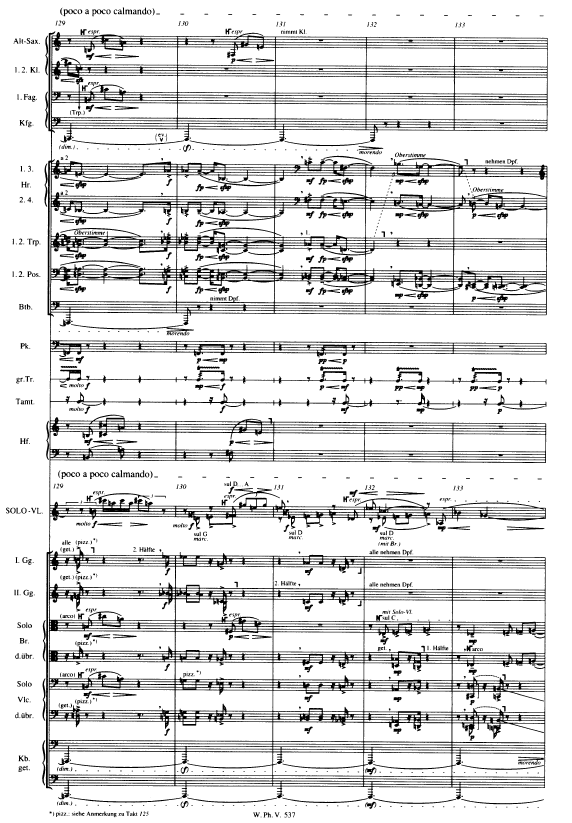

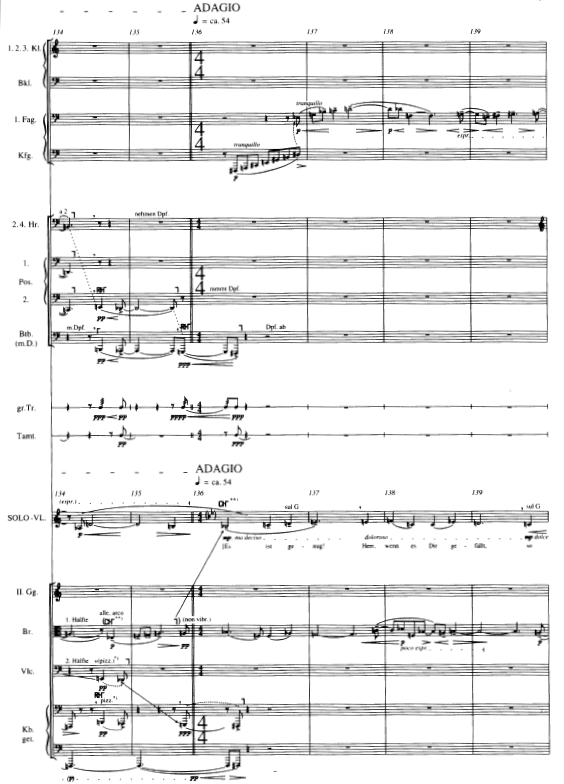

His opera Wozzeck is practically a textbook of compositional forms. But I’ve chosen the most famous passage from his Violin Concerto to illustrate how he so skillfully combined vastly different musical worlds:

Berg’s going from a huge dissonant cluster to a quotation of Bach. What’s admirable is the smooveness with which he does it: the chorale melody starts with a rising 4-note motive. He introduces this motive in the violin during the most dissonant music. Then he gives us the tune, but it’s set against slightly less dissonant music. By the time the winds enter on Bach’s harmonization, it makes all the sense in the world.

Discuss

So, in choosing the composers on this list, I think I settled on the following criteria for great compositional technique:

1) handling of counterpoint (multiple, simultaneous lines)

2) tight motivic construction (building melodies and sections of music out of small themelets)

3) form (a logical succession of musical ideas, paced correctly so that the music seems to follow a logical flow)

4) ability to contrast and unite disparate musical ideas (which nobody does better than Schnittke, and I hate not including him on this list)

And then there’s the matter of, given their resources, how well did these guys write the stuff down on a score? Sibelius is one of my favorite composers, but his scores are a certifiable mess when it comes to logic and consistency. Ligeti’s scores are nearly as virtuosic in their meticulous layout and instructions as they are in their musical content.

So, y’all, what do you make of these criteria? And who fits it? My guys, or some other peops?

If you’ve made it this far, it’s time to let your voice be heard in the comments section!

I was waiting for this list, and am glad it arrived! And your winners are very thoroughly and impressively presented.

I tend to think of Ravel as the ultimate craftsman/watchmaker/etc, so I’d probably put him in over Debussy. Just seems like Ravel could do anything he wanted to do.

This might also be the spot where I’d give Mendelssohn some props. I’ve been listening to the violin concerto a lot lately, and I just find it completely flawless – the formal perfection of the 1st movement is amazing and my interest never wanes, even though I’ve heard it hundreds of times. And the Octet!!!

Oddly, as much as I love Brahms, I sometimes feel he’s working too hard with some of his clevernesses. Some of this rhythmic/metric tricks are cool, and sometimes it’s just, “again, with the hemiolas?”

And though Haydn probably is as great a craftsman as Mendelssohn or Ravel, I just don’t respond to much Haydn the way others do. A personal blindspot, I suppose. But I am curious, which are the melodies that show Haydn to be “really good” at that? I think even Beethoven’s a better tunesmith than Haydn. I think Haydn’s artsongs are some of the worst music I’ve ever had to play as an accompanist. I’m replacing Haydn with Shostakovich, who just seems ridiculously virtuosic as a composer. Gorgeous tunes, stunning fugues, enormous canvases, charming miniatures.

I’ll admit that Berg, Ockeghem, and Ligeti don’t mean so much to me, but you’ve offered wonderful evidence on their behalves.

By the way, that Bernstein on Beethoven video fascinates me. First of all, he’s basically repeating, almost verbatim, the Beethoven argument he lays out in the “Bull Session in the Rockies” chapter of “The Joy of Music.” (I know, because I’ve probably read that chapter 20 times!) So, it’s a little odd to have him retreading this same argument so conversationally (pretending to discover the word “inevitability” for example) 20 years later; though, in fairness, he was a busy guy, so I can’t blame him for bringing back old material. And it’s pretty good material.

And then there’s the cigarettes. The worshipful guy sitting and listening seems to be thinking, “if I just keep smoking like a chimney, some day I’ll be as wise and basso as Lenny.”

…oh, the worshipful guy is Maximilian Schell. I knew he looked familiar.

Michael:

Lot to discuss here:

1) Yes, it most definitely is Maximilian Schell, who seems to have a cottage industry in hanging out w/ famous conductors and appearing with them on film (there used to be this DVD called “The Silence that follows the Music” that features him having an elegant dinner and cigars w/ Claudio Abbado as they talk about music… amazingly, there is no YouTube account of this seminal event).

2) Lenny playing the character of Leonard Bernstein is in fact the best thing ever, EVER. And there’s no doubt that Lenny smoked his natural tessitura down a good octave.

3) I really want to talk about Ravel, who I can promise you will see on my personal faves list. Of course he is as deserving as just about anybody to be on this list. I feel that he essentially falls into the Beethoven camp of compositional technique – that is, I think his greatest strength is a penchant for harmonic rhythm and form. The first section of “Daphnis et Chloe” is a case in point and reminds me great deal of the “Pastoral” Symphony in the way Ravel builds a large structure one bar of harmony at a time.

So, in an alternate universe where I made this list like 5 minutes later or earlier or something, he would definitely be on the list. But I think he would probably replace Haydn instead of Debussy. I hate to pit Ravel and Debussy against one another as they have so relentlessly been pitted throughout history. I think it’s a different kind of compositional intelligence at work, even if some of their aims were the same and the results similar-sounding. I think Debussy was a magnificent contrapuntalist in a way that Ravel wasn’t quite. I also think he was about as specific a notater (notator?) as you’re going to find. In the introduction to Clint Nieweg’s edition of “La Mer”, the editor points out that Debussy uses something like 15 distinct articulation marks. Crazy!

4) You know, it’s funny, because I do consider Haydn this incredibly tuneful composer, but I don’t know if I could point to one example of a great melody from him. Certainly I didn’t list him among the great melodists. Touché.

5) Mendelssohn. Yes, agreed, there’s a startling amount of perfection going on there. Objectively, maybe he should be on this list. Subjectively, I love a lot of his music, but I’m just not terribly close to the guy.

6) I’ll take this opportunity to go on the record with my feelings about Shostakovich.* First off, I would never even consider including him on this list. However, I do not think he was a bad composer – quite to the contrary, I feel Shostakovich was a great composer – in search of a great editor. That is to say, I think he wrote some amazing music, but for some reason he felt a need to surround those really great chunks with extensive passages of drab contrapuntal meandering. Every one of his symphonies is about 1/3 – 1/2 boring. If he had just had someone to help him out with this, or if he had gone back and edited down most of his pieces to 1/2 – 2/3rds of their length, I’d say he would be one of the best composers.

But, perhaps there’s a point to be made here: a composer has to be his own editor, so do we include that among his compositional talents? Obviously I do. But maybe a composer lacking great editorial powers can still be a great composer? hmm….

Time to get a whittling! Ima do this in categories of agreement.

First: Yes indeed!

Ockeghem, Brahms, Mozart, Haydn, Berg. No doubt.

Second: Sacrilege if I disagree. But…

Bach. If you actually get to thinking about it, he’s sort of a curious case. It’s old news that you can’t teach Bach to a counterpoint class…because his counterpoint is bad. From a Fuxian perspective. So, in a way, if you’ll indulge me, he’s sort of not a technical bad ass…except for the fact that he somehow manages to break every rule ever all the time and it still works. Brilliantly. So, in a way, it’s like he’s really just a bad ass rather than a technical bad ass. Kinda feel like I’m digging my own hole, but, you know what I mean?

Third: I understand, but no.

Beethoven, Debussy, and Ligeti. Love all three, but I’m not sure they really fit the criteria. Sure, all have major chops, but I don’t think any would win in a fugue-off. Usually this would sound derogatory, which is hardly my intent, but these are composers who are good at what they do. I save myself by saying that what they do is brilliant beyond belief, but I don’t like to think of it as a technical thing. Perhaps what I’m getting at is that I consider them all to be top-shelf composers, but not ones I would characterize by their technical merits. In order to be a composer of any worth, you need to have chops, which these cats do, but I don’t see them as really flaunting it like the others I want on the list. Your arguments (or Lenny’s) are quite sound, but I’m going to try to come up with some people who might be a little more apt.

Fourth: No. Just no.

Stravinsky. Really? Technical awesomeness? There’s a lot the man did brilliantly, some of which certainly ventures into the realm of compositional virtuosity, but I think there are just way too many holes. Obviously, his music works – I’m not debating that. There’s no questioning that he’s a great composer. But I don’t buy into that “Bach on the wrong notes” thing. I think he had a sound, there are some pretty wicked technical components to it, but the same could be said of Barber, Copland, and a whole host of others. Perhaps what’s at work is the fact that Stravinsky took such an idiosyncratic approach to things that we think it’s profound technical work (and again, sometimes it is), but I wouldn’t put him next to Ockeghem.

Fifth: Alternatives.

Thomas Adès, Elliott Carter, Milton Babbitt, and Gesualdo.

If there are any bad asses who know their shit out there today, it’s Adès. I’m pretty sure he speaks for himself.

Carter I present as my Stravinsky alternative. Old Igor is showing his best stuff when he’s dealing with rhythm, but I think integration is where Carter pulls ahead. Sure, Iggy had his own way of dealing with things, but we’re still scratching our heads over it while Carter’s music has an obvious cohesion that’s really pretty awesome from a technical perspective.

Babbitt’s music, like that of Adès, sort of speaks for itself. I know he tends not to “move” quite as many people as most on this list, but that’s a pretty subjective (and lame) criterion. The fact remains that the man p0wned the set class shizzle like none other. And that is not easy.

Likewise, Gesualdo p0wned the counterpoint! For as radical as his music sounds, very rarely (if ever) does it violate any principals of good counterpoint and if you can work in chromatic mediant relations without violating modal procedures and traditional rules for the treatment of dissonance, you win at life. Apparently, murder is secondary.

Sixth: alternative alternatives.

Bartok. I could very easily have put him on my list and would maybe even consider trading him for one of my definites. The man set up a system just as rigorous, if not more so, as the others associated with people on the list and dealt with it fearlessly. His Kung Fu is strong.

Cher monsieur le Provocateur,

First: Good

Second: You must be kidding me.

I seem to recall learning all my counterpoint from Bach. Well, not exactly, but we certainly relied pretty heavily on the 2- & 3-part inventions along with the WTC. Maybe that’s why my counterpoint sucks, you might say!

It would be one thing if Bach broke the rules because he was unable to follow them correctly, but I believe for a second that that’s what you think. WHEN Bach broke the rules (which was hardly “all the time”, it was because he CHOSE to break the rules at that moment. I’d be willing to bet that the grand majority of his contrapuntal writing breaks none of the rules (or none of the major ones at least 🙂

Third: This might be a matter of weighting. I listed four criteria that I ended up with after making my list. They’re sort of in descending order of importance. But I’m willing to include composers who weigh particularly strongly in one area, like Beethoven in the matter of “form” for want of a better word. But honestly, enough of this Ludwig bashing when it comes to counterpoint. Has nobody listened to the Grosse Fugue?? It’s, um, awfully badass, don’t you think??

Fourth: I’ll agree that Stravinsky is sort of a stretch – but not by much.

Fifth: Yeah, the ‘Dès got it goin on for sure. I’ve never seen anyone make quite as extensive use of non-powers of two and actually seem to know what it means, so props. I like the guy, for sure, and I think he does a great many things excellently. I think he sometimes lacks in the pacing department though – his operas run a little too Britten-y for my liking. And they’re a little to opera-y for English. But I’ll still buy it.

Carter & Babbitt: as my teacher used to say, nothing is easier to write than a 6-part retrograde-inverted mensuration cannon at the tritone if you don’t care what it sounds like. You’re not the only one who can be provocative around here.

No but srsly, Carter I did consider putting on the list. Some of that stuff he did with tempo is pretty badass technically. I once went to a concert of all five Carter quartets played back to back. After such an experience I can not in good conscience put him on any list.

Sixth: Yeah. Bartok. Totally.

I feel like I need to offer a rebuttal just to ensure that I don’t like like an imbecile. Really, I’m partly kidding in re: JSB. Likewise, I learned a lot of my counterpoint from the inventions, but I think those lessons really said more about how to write compelling polyphony than technically sound counterpoint. Since the two-parts reflect pretty much the limit of pianistic skills, they’ve become very familiar to me and, though you won’t find too many parallel fifths, the old man’s treatment of dissonance is definitely suspect. That’s what I mean by rule breaking: to me, his M.O. seems to revolve around making multi-voiced textures comprised of voices that are as independent as possible, packed with the tightest motivic unity imaginable, and with a brilliant sense of melodic shape. All of this, consequently, is in deference to more rigorous aspects of the practice. Obviously he was well aware of what he was doing and absolutely could have colored between the lines if he wanted to, but such was just not his interest. I think what we might be up against is a discussion not of his technical proficiency, but of how Bach as an individual developed and flourished within his own set of stylistic priorities. Maybe this renders the issue into another question weighting, but so it goes. This would make for a good bar discussion…

…but on to other matters. I dare say you’re being too cruel to Mssrs. Babbitt and Carter. I’m not sure a concert of anyone’s complete quartets in a row would be a good idea. Too many notes. And – I’m pretty sure Babbitt cared very much about what his music sounded like. As nerdy and cerebral as he was, I don’t think we can write off his deep artistic ambitions. As a smart little cockroach once said, “expression is the need of my soul;” I think Milton just needed hexachordal combinatoriality to say what he wanted to say.

Oh – and: I think Beethoven is perfectly fine at counterpoint and Die Große Fuge is, to be sure, bad ass. However, I still don’t think he’d win in a fugue-off. Brilliant though he may have been, all those endless sketches and scribbles make me pretty sure his brain wasn’t wired for that sort of competition. Then again, not many people’s are.

The second you bring Archie into the discussion, winning commences.

Sorry, it’s not often I get 2 use a relevant cultural meme.