Day 1 in my audacious response to Anthony Tommasini’s Wild and CRRRAzy idea of choosing the top 10 composers. Today, we focus on Innovation and Originality. Which composers took the boldest risks and were willing to suffer the consequences? Which composers were marked by thinking of musical ideas and sounds that simply nobody had ever thought of before?

I’ll further define this list in opposition to tomorrow’s list. Tomorrow, we’ll look at the Top 10 Most Influential Composers. Today’s composers could all be cul-de-sacs in musical history – no later composer need have taken up their particular style or innovations. We’re talking about brazen, unfettered originality for originality’s sake.

1. Hector Berlioz (1803 – 1869)

For my money, Berlioz is the greatest musical innovator. His experiments often failed, but they never lacked for ambition. Every piece was grander, bolder, and less practical than the next, beginning with the Symphony Fantastique and continuing up to his sprawling 4 1/2 hour opera Les Troyens. Berlioz never wrote in a prescribed form: he preferred inventing them. He created tone poem-symphonies (Fantastique), symphony-concertos (Harold in Italy), and even bold admixtures of drama, narration, art song, and choral symphony (Lélio).

Before Berlioz, composers had depicted birds chirping, storms raging, and the rolling seas. Berlioz depicted opium hazes, witch’s covens, and rolling heads:

2. Carlo Gesualdo (1566 – 1613)

The Renaissance Italian prince is primarily known for two things: 1) finding his wife in flagrante with her lover and subsequently murdering them both (which, btw, was not only his prerogative, but his duty as a member of the nobility) and 2) composing Renaissance madrigals that made use of outlandish, expressionist harmonies. Anybody who writes something like this in the 16th century is pretty original:

(Beltà poiché t’assenti, Concerto Italiano)

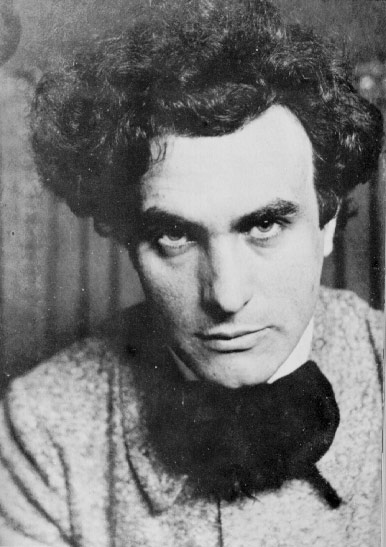

3. Arnold Sch̦nberg (1874 Р1951)

In a lot of ways, the music that lead up to Schönberg’s radical departure from tradition did pave his way: Mahler and Strauss and Zemlinsky and those types were already stretching the boundaries of the Tonal system of chords and scales. But Schönberg took their groundwork in much bolder directions. He then concocted, out of thin air, a mathematical re-imagining of how notes could be structured into music – that is a real innovation, and that’s exactly what Schönberg did with his 12-tone system in 1921.

The results are sometimes strangely beautiful. Sometimes, they are unspeakably ugly. Usually, they are at least cool:

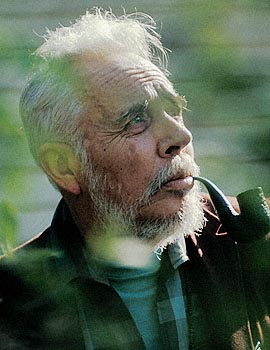

4. Harry Partch (1901 – 1974)

How much more original can you get than inventing your own instruments, scales, notational system, and musical language? I mean, what’s even going on in this score for “Delusion of the Fury“?

While there’s no denying that everyone on this list had plenty of influences, Partch really stands out as an individualist. What planet did he wander in from to write this?:

5. Claudio Monteverdi (1567 – 1643)

David Ewen writes:

Compared to the archaic vocabulary and methods of his predecessors, Monteverdi’s operas represent an entirely new art. This is not a revolution: there was nothing before Monteverdi that he could have revolutionized. This is invention, the discovery of a brave, new world. He was the first one to understand and appreciate the role of the orchestra in an opera, to use an instrumental style and resources as an ally for his dramatic mission. To use instruments for the purpose of mood painting and characterization was simply without precedent. He knew how to make his characters not the abstractions they had been before, but human beings.

(Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda, Concerto Italiano)

6. Edgard Var̬se (1883 Р1965)

This French-American composer wrote the first piece for an ensemble made up exclusively of percussion instruments: Ionisation from 1931. Many composers invented ensembles, but percussion instruments lack one vital element of music: pitches. [Usually.] In eliminating all reference to traditional pitch systems and leaving himself with only rhythm, timbre, and dynamics, Varèse forced himself to create a musical language all his own.

Even when he did use more traditional instruments and ensembles, his music displays an undeniable individuality that was not linked with any of the prevailing trends in musical modernism. That he later turned to electronic composition in the 1950’s simply confirms his ever-curious musical mind.

(Ionisation, Die Reihe Ensemble/Cerha)

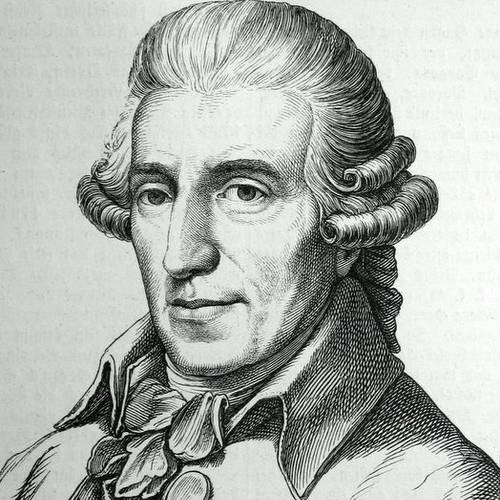

7. Franz Joseph Haydn (1732 – 1809)

Please let’s not forget about everything Haydn did while he was toiling away in an obscure Hungarian field somewhere: he invented the symphonic form (four movements, fast – slow – minuet – faster), modernized the orchestra, invented the string quartet – both as a genre and as an ensemble (although, can you really separate the two?), and totally revolutionized musical language. He is also the first composer to ever make significant use of folk music as source material for his compositions.

Suffice to say, when he started writing music, it sounded like this:

(Symphony No. 8, Austro-Hungarian Haydn Orch/Fischer)

and when he finished, it sounded like this:

(The Creation, LSO/Colin Davis)

8. Igor Stravinsky (1876 – 1963)

I know that Igor Stravinsky stole left, right, and center from Debussy, Ravel, Rimsky-Korsakov, and probably a lot of other people. But did any of them write this?

(The Rite of Spring, LSO/Davis)

I didn’t think so.

9. LeoÅ¡ JanáÄek (1854 – 1928)

This Czech composer was a really late bloomer – his early works were indebted to a folkloric, watered-down version of Brahms that he received via Dvorak. And then, something happened – maybe it had to do with the death of his daughter, perhaps with his increasing fame and prosperity, but slowly and late in life, he forged a deeply personal style, especially in opera.

JanáÄek was everything you’d expect from an eccentric, craggy composer – he was an ill-tempered and obstinate man. His radical style often sounds like it:

(String Quartet No. 1, Melos Quartet)

10. Claude Debussy (1862 – 1918)

Almost all the composers listed above were chosen because they created brash, aggressive, dramatic new sounds. Debussy did just the opposite – he explored the many cool, washy colors that classical instrumentation had to offer.

It’s really important to remember that Impressionists in music and Impressionists in visual art may have ended up with “similar” effects, but they came at it from totally different starting points: whereas Visual Impressionists were trying to add vagueness and mood to their canvasses (so as to lessen distinction and increase the sense of an “impression”), Debussy was doing the exact opposite – he was trying to enrich his musical language so that sounds could actually turn into musical scenes with literal places and characters.

His real innovation was to combine the mellifluous sounds of Indonesian gamelan music with the greatly expanded harmonic palette of Wagner and Massenet. Thus:

(Ibéria, Cleveland Orch/Boulez)

Talk Amongst Yourselves

I’m going to resist the temptation to write about all of my notable mentions, because that would defeat the purpose of just putting up 10 people, and plus, the whole point of this exercise is the discussion. Your job now is to argue with me and point out all of the people I either stupidly left out or stupidly included.

My only request is that if you propose a composerly alternative to any of my suggestions, please specify who you would like to remove from my list to be replaced with your contestant.

More than anything, I’d like to hear your all’s Top 10 Most Innovative Composers Lists.

Let the games begin.

Paganini?

Tenola – when I first read your comment, I scoffed. But then I thought about it a little more, and he certainly did a hell of a lot to increase the technique of violin playing. I think he’ll be a very strong contender on my upcoming “Top 10 Genre Composers” for “Violin Music”.

Love this post; love your list. One composer that immediately comes to mind for me is Mahler. Perhaps he doesn’t fit your definition of innovative (and I think you did a good job of clearly defining it), because so much of what he did was clearly built upon the work of his predecessors. But, when I hear his music, I feel as if he discovered how to multiply, exponentially, the emotional forces of music. And that should count for something, I think. As to whom I would replace…that’s tough. Perhaps Gesualdo, because I’ve heard quite a few other wacky examples of vocal writing from the 16th century. Although – who knows? Maybe they were Gesualdo. Another composer that comes to mind, as a vocalist, is Ives. And hey, no Britten? Okay, lists like this are hard!

Leann – yes, I totally agree, Mahler would be an excellent choice, the 7th symphony in particular strikes me as really out there and daring. But I think he got a lot of ideas from Wagner and Verdi. In terms of instrumental technique, I think Strauss probably pushed things further. And I think Zemlinsky was probably a little more daring with harmony, but that’s more a guess.

I totally know what you’re saying about Gesualdo – there’s all of these other guys like Luzzaschi who were also using tertial chord relationships and other assorted weirdness, but I still think Gesualdo takes the cake. I’m likely very influenced by the fact of those murders that he committed.

Ives is someone I STRONGLY considered putting on the list… and you know why I finally didn’t? Because I thought he was too influenced by Mahler!! hahahaha. Yeah, these lists are hard, and probably Ives never even heard a note of Mahler’s music when he wrote his stuff, but that’s also very complicated because Ives lied about a lot of the dates of his music.

Hope you’ll tune in for the rest of this thrilling endeavor… 😉

I must say I agree with a lot of your choices, but for me Beethoven must be on there. I believe he changed the course of music history more than any other composer, and some of the things he does in his late string quartets are just so far ahead of his time. However, this is quite a task you have set in front of you!! I hope you’re well, man. 🙂

Conner – not so quick! I agree, Beethoven seems like a really obvious choice for this list and it was really hard not to put him on there. BUT, you haven’t finished playing the game until you remove another name from the list. Not so easy, is it?

Two words: John Williams.

Perhaps you jest, anonymous Bureau Chief from LA, but don’t be surprised if you see his name pop up in one of the 9 remaining lists… can you guess which one?

This is a fun list, but several other names immediately came to mind: I would replace Janacek, Haydn, Partch, and Gesualdoto with Beethoven, Ligeti, Ives, and Reich.

John – All totally valid choices, and certainly on the larger list that I narrowed down to come up with this one. I don’t see how you could take Harry Partch off the list though.

As for Gesualdo, something I forgot to mention in my reply to Leann is that he was likely writing for an extended mean-tone tuning system equivalent to 31 notes per octave, so I think there’s more weirdness to be explored than we often hear in recordings. I still want to keep him.

I wouldn’t include someone just for being weird. I’d chose Stockhausen, Messiaen, John Cage, Lou Harrison, or John Williams in place of Partch.

Top 10 Most Biggest House?

R. Kelly

In: Scriabin

Out: Janacek

In: Sibelius

Out: Gesualdo

Interesting – I’d love to know your reasoning. I agree that both of these guys were innovators, but was Scriabin really that original? A lot of his music sounds to me like Chopin and Liszt. And Sibelius? A lot of influence of Wagner and Tchaikovsky. Again, that’s not to say that he wasn’t an innovator, and particularly the things he did with form later in his career strike me as quite revolutionary… But why replace the two that you did?

I second the Stockhausen nominations. Much of the rationale behind putting Varese on the list could very well be applied to dear old Karlheinz, but he also deserves mega props for also expanding the possibilities of serialism, just intonation, and improvisation each in a profoundly unique fashion.

And for a does of obscurity/obnoxiousness, I want to throw out the name of Anton Reicha. A buddy of Beethoven, he performed critical experiments with polytonality, meter (including irregular meters and polymeter), form, harmony, and basically every other musical parameter ever…all before he kicked the bucket in 1836. So while Berlioz was in his opium haze (not that I have an issue with his inclusion on the list), Reich was down the street in Paris writing fugues in 5/4 with progressive tonal structures. Granted, it took until, say, now for anybody to actually absorb his ideas in the ways he intended, but I’d say he fits your criteria. But who to replace? Oy. Ima say Janacek. True, he’s a badass, but I think his innovations were a long time in the making. Same with Bartok, in a way, but that’s another story.

Gabe – INTERESTING! I must now buy every Reicha recording I can get my hands on!

I suppose you’re right about Janacek. I guess I always think of him in this respect because it’s like, really? Janacek wrote that?

I would have thought putting John Cage on this list would be a no-brainer. I like John Williams just fine, but I find it strange to see that he’s mentioned as “innovative”.

Personally, I’d include Frank Zappa.

Mr. Stein,

I agree entirely about John Cage. I considered him thoroughly in fashioning this list. In fact, if I were to re-make the list, I might well include him. Certainly he held a revolutionary perspective on what Music could be. In the end, I think I chose not to include him because I thought there’s a lot of Henry Cowell in his music. Or maybe it’s just because I don’t really like his music. It is so hard to keep from letting one’s personal opinion get involved (not that I much care for Schoenberg…)

As for Frank Zappa, I wonder if you could help educate me – does he qualify for our definition of “composer”? That is to say, did he actually write his music down? I plead ignorance!

Sibelius’ formal experiments were on my mind when I named him. I know he had predecessors in that regard; maybe it’s the difficulty he had writing good transitions that makes his activities seem especially daring. Then again, perhaps that shortcoming lends the results their unique flavor.

Like one of the other commenters, my sense of Gesualdo is as one of a few Renaissance composers whose forays, while striking, don’t merit precedence over any of the others’.

The Scriabin I’ve heard presents its constituent materials in an unpredictable motivic constellation. I don’t know any other music where this practically anti-developmental technique is so pronounced. Then there’s textural adventuring in the late sonatas, attempts at mixed-media inducements of synaesthesia, and the unfulfilled dream of Mysterium (does it count among his innovations even if he was just THINKING about it?)

All of that, I think, reaches beyond the scope of Janacek’s innovations.

Is “Mysterium” that thing that was supposed to be like, on a mountain or something?

Will, as much as I admire your innovation in this list of innovators, I must insist on the inclusion of an all-too-familiar personality: Herr Wagner. I wouldn’t deprive M. Berlioz of his standing here, but intention alone cannot define greatness of innovation. It was Wagner who actually succeeded in fulfilling (and, I feel, transcending) the aesthetic aspirations of that audacious Frenchman.

Mike,

It did indeed pain me not to include Wagner on my list. But, if you are suggesting that he should replace Berlioz, I would have to raise some serious points of contention. I guess the first bone to pick would be that I’m not looking for “greatness of innovation”. In that respect, I think you could rightly claim Wagner over Berlioz. I’m just looking for boldness and originality of new ideas, be they great or horribly flawed.

Will,

Fair enough. Allow me, however, to state my feelings more simply: the two boldest and most original pieces ever composed are The Rite of Spring and TRISTAN.

Oh also – I just remembered Alois Haba. The dude founded an institute for quarter-tone studies in Prague…in the 1920s. Wowzers! If you find any of his stuff (including music in quarter-, and fifth-, and twelfth-tone systems), consider yourself lucky. Da. Bomb.

Gabe –

Re: quarter tone composers – did you know that Halévy, the guy who wrote “La Juive”, wrote a quarter-tone cantata in 1848 or some shit?

Oh snap! He features prominently in my composition teacher genealogy. C’est tres bizarre! A new recording i must now travel the Earth in search of…

I KNOW!! but you will have to look high and low – as far as I know, nary a recording exists of said bizarrity!

If you find one, you must play it unto me.

Will – yes, Zappa wrote his stuff down. Google “Zappa Scores” and you can find a lot of his stuff. (It was just a facetious suggestion, but he did do more exploring of the rock/classical boundaries than anyone else I can think of.)