La La Land is a movie I should have enjoyed, what with the singing and the dancing and its many references to classic Hollywood movie musicals and 60’s French jazz style – my very bread and butter! And occasionally I did enjoy it, but most of the time I just had this nagging feeling that something, or a lot of things rather, were missing.

There’s two basic approaches to a movie that trades in this brand of nostalgia:

- you tell a deeply felt story using an anachronistic style enriched with contemporary detail/sensibility to give it a new texture and a timeless feel or

- you do a loving, high camp homage that is all about style, recontextualizing/repurposing/juxtaposing it as the very clay in your hands.

or you know, some combination of both. Which is what I think La La Land was trying to do, but ended up doing neither, or, perhaps more charitably, did such a watered-down version of both that it canceled itself out and left us clad in GAP khakis when we’d rather be swaddled in mink stoles.

Strategy #1: historical style X contemporary detail = a new story imbued with a sense of timelessness

If you’re going to do this, you have to put a lot of thought into the details, because therein lies the interest and texture of the film (/play/opera/musical/project). Almodóvar does this even when he’s nominally going for the campier (#2) approach. He can’t help it.

So if you’re going to make a movie about a contemporary jazz pianist whose main struggle is one of artistic freedom v. societal norms and expectations it would maybe help to get the details right about what a contemporary jazz artist looks like w/r/t the realities of the music and such a career.

Now. Our protagonist’s basic musical sensibility is ‘pure jazz’ = McCoy Tynerish post-bop, ‘free jazz’ = Claude Bolling Writes a Cadenza, and ‘sell-out jazz’ = mid-career Stevie Wonder.

And you know, there are those dudes out there who are still into the post-bop purist thing, but if that’s what we’re going for, let’s go for it, especially in the music. The score, which consists of six original songs, isn’t bad but it definitely doesn’t go there. Harmonically, the songs hover in a mildly jazzy 5-to-6 chord pop fusion area, when they might instead ascend to a more complex 10-to-12 chord jazz standard territory, or even 8-to-9 chord broadway showtune territory – can someone give me a straight up secondary dominant up here??

[Cred where she be due though: the composer, Justin Hurwitz, wrote not only the songs, but the entire score, including the orchestration, a rarity in Hollywood, and I loved some of his orchestrational touches, with obvious nods to Philippe Rombi (Angel, for example) and the Björk/Vincent Mendoza collaboration on Dancer in the Dark (though I longed for that score’s kaleidoscopic brilliance!)]

Our protagonist isn’t only angry with every post-Weather Report development jazz, he’s also upset that his former club is now a “tapas and samba” place – as if that didn’t sound like a veritable match made in heaven! It seems to me like a more interesting and plot-consistent take on the new place would be if it were cast as a pop/hip-hop venue, aka the music of our very time.

But mentioning hip-hop or other Contemporary Urban Musicks would veer us into a whole racial dynamic that Mr. Chazelle seems very squeamish about, and any time the film strays too far into said territory it reveals a nervous tokenism. (Two lily-white protagonists? Fill up your jazz club with black people! That’s not what most jazz clubs look like these days, but hey, you stay balanced.)

Strategy #2:Â historical style X heightened/deconstructed detail = high camp (which often turns out to be a potent delivery system for a serious messages about our own time)

Chazelle leans more towards this approach and he has some successful moments. My favorite was the dream ballet at the end (whatup Agnes!!) with its use of On The Town style backdrops set on a studio soundstage and its nods to Jerome Robbins choreography.

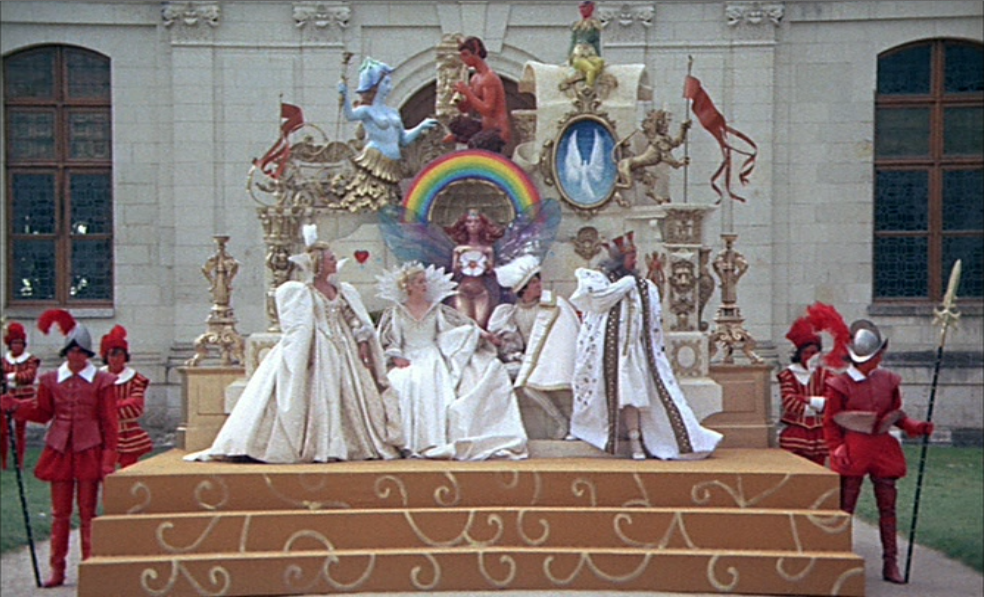

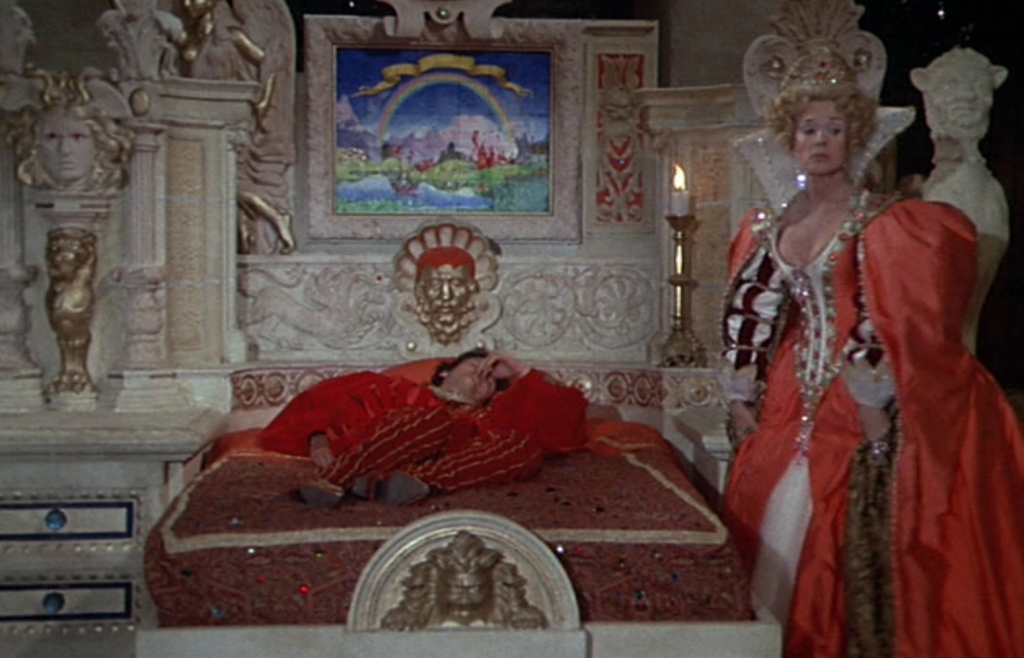

Jacques Demy is a big influence on the film too, particularly Les Demoiselles de Rochefort. But it’s like, whatever you use as your starting point, you gotta Next Level that shit, and that’s hard to do with Demy, because his approach to film style and fantasy are already pretty gonzo (have you seen, par example, Peau d’âne??)

François Ozon is a director who loves to play pastiche with the likes of Demy and Minelli and these old Hollywood musicals and it’s worth comparing his work with Chazelle’s. In Water Drops on Burning Rocks, 8 Femmes, and Angel, Ozon imbues his stylistic allusions with a zany irreverence and a free spirit that makes La La Land look clichéd.

And here’s the secret about these two approaches: you don’t have to pick just one! Get you a man who can do both! You know how there’s “Serious Almodóvar” and “Playful Almodóvar”? Guess what girl – she the same mofo!!!

In Conclusion

Am I being too mean? The Dream Ballet, the Observatory sequence, the opening party were all fun and interesting and good. The movie offered these and other magical moments where the combination of picture and score set sail (flute trillz be praised y’all!)

But the stakes were low, and I can only imagine the protagonists’ bland trade-offs are indicative of Damien Chazelle’s rather frictionless career. This struck me as an honest movie, just not an interesting one.

And I’m not suggesting that he should write a gritty, racially-charged story of an out-of-control artist struggling with abuse. If he had just imbued this particular story with a richer level of detail and zestier approach to style, it would have burst off the screen instead of just sitting there. For a movie about lives not lived and paths not taken, there were an awful lot of missed opportunities.

Nothing beats a good old fashioned waltz. I use them in my

Nothing beats a good old fashioned waltz. I use them in my  Leave it to an Irishman to best the English at their own game. The English choral tradition is a quite specific thing. There’s the whole issue of dueling churches, the Anglican and the Catholic. Certain composers specialized in one or the other. Certain composers were glad to be denominational mercenaries.

Leave it to an Irishman to best the English at their own game. The English choral tradition is a quite specific thing. There’s the whole issue of dueling churches, the Anglican and the Catholic. Certain composers specialized in one or the other. Certain composers were glad to be denominational mercenaries. What I love about Weill’s songs is how sardonic they are. He displays a remarkably dark wit in the interplay of his spiky harmonies with the light lyrics (which he didn’t write). His music represents the gritty world that his characters inhabit.

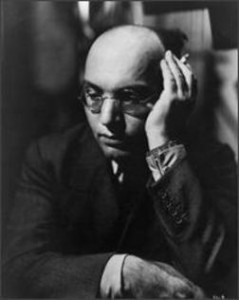

What I love about Weill’s songs is how sardonic they are. He displays a remarkably dark wit in the interplay of his spiky harmonies with the light lyrics (which he didn’t write). His music represents the gritty world that his characters inhabit.

Aside from

Aside from