Osvaldo Golijov (1960 – )

Osvaldo Golijov (1960 – )

Sidereus

Osvaldo Golijov is the composer of such blockbuster classical hits as The Dreams and Prayers of Isaac the Blind and the toe-tapping Pasión según San Marco:

Mr. Golijov’s pieces often have more the flavor of an ethnomusicological exploration, which makes a certain amount of sense for a composer of Argentinian birth who grew up on klezmer and tango and who has also lived in Israel and the U.S. [Although, is it really ethnomusicological if it’s actually your ethnicity? Discuss.]

Anyone who attended Thursday’s lecture was privy to insights from the work’s dedicatee, Mr. Henry Fogel. Boosey & Hawkes has provided an equally enlightening interview with the composer about the genesis of the work. You can listen to the work online in a performance conducted by Mei-Ann Chen (who gave the première in October 2010 in Memphis) with the New England Conservatory Philharmonia. Also of note is Mr. Golijov’s growing filmography since becoming the go-to composer of Francis Ford Coppola.

Lest there be any confusion, the title of Mr. Golijov’s latest work, Sidereus, is in no way meant to sound like an hilarious mispronunciation of the next composer on the program.

Jean Sibelius (1865 – 1957)

Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 47 (1903, rev. 1905)

Sibelius’ violin concerto is far and above my favorite work in the genre, and one of my favorite works by the composer. In fact, it’s one of the first pieces that got me into classical music. You can view an introduction to the work here by the violinist Ida Haendel, who actually received a letter of appreciation from Sibelius after he had heard her performance of the work, and whose Wikipedia entry actually says the following:

She has the reputation of being as accomplished and brilliant a violinist as Yehudi Menuhin and Isaac Stern; but has said that had she been more photogenic, she would have been as famous.

Ida Haendel

Yehudi Menuhin and Isaac Stern, two violinists who Ida Haendel was not as attractive as

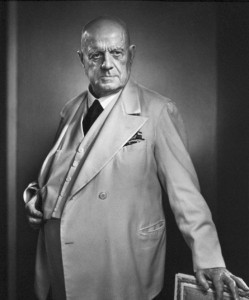

People sometimes said the same thing about Sibelius himself, but never to his face (see above).

But seriously folks, if you’re really into the Sibelius concerto, it’s worth your 10 bucks to invest in Leonidas Kavakos’ recording of the 1903 and 1905 versions of the work. He is still the only artist to record the 1903 version, due to the Sibelius family’s wishes, which is pretty impressive. He is also way, way hotter than Ida Haendel.

You’ll get to hear the intricate, Bach-like second cadenza that Sibelius later cut from the first movement of his concerto:

amongst many other interesting tidbits.

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906 – 1975)

Suite from Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District

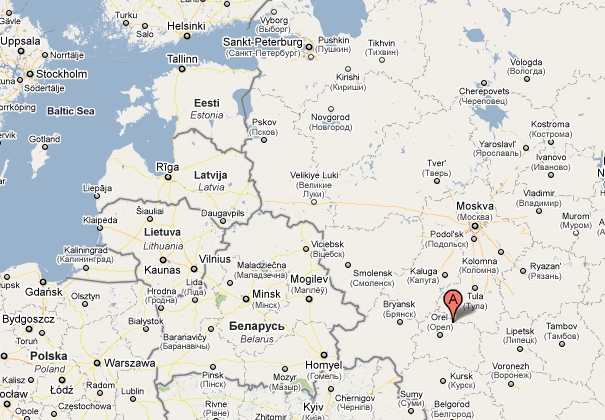

OK, first of all, if you’re anything like me, you’ve always wondered just where IS the Mtsensk District. It’s here:

The rest of this discussion I’m gonna cut and paste from my March 4, 2010 post about Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 11:

Shostakovich’s troubles with the government began in the year 1936, at which point Joseph Stalin, eager to send a message to the artistic community, denounced Shostakovitch’s opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District as immoral and anti-soviet. Let’s watch a bit of the opera and see if we can spot anything that Stalin may have found objectionable. Remember to look very closely now:

At first glance, it looks pretty tame, but that Stalin always had a fine eye for detail. Anyhoo, that led to this very famous headline from the Soviet newspaper Pravda:

which roughly translates to “Muddle instead of Musicâ€, and which began a nightmarish 20 year period of heavy government repression and scare tactics aimed at keeping Shostakovitch in line.

I’d like to recommend two more valuable resources pertaining to Shostakovich’s music and life:

The first is the audio guide to chapter 7 of Alex Ross’s phenomenal book, The Rest is Noise. Even if you haven’t read the book or don’t have a copy handy, the audio guide gives you a nice synopsis of the chapter on music in the 1930′s and 40′s USSR.

The second is an article by everybody’s favorite Slovenian Marxist-Lacanian-psychoanalytic philosopher, Slavoj Žižek, entitled “Shostakovich in Casablanca“. In this article, Žižek compares Soviet repression of classical music to the Hollywood Hays code, in terms of what the censors expected and how an artist was meant both to abide by the code and simultaneously to circumvent it. He posits that Shostakovich found whatever success he could with the Soviet regime because he understood this Janus-faced censorship, whereas Prokofiev just couldn’t figure it out.