On a recent program, the local symphony orchestra included a movement from the reconstructed “10th” symphony by Franz Schubert, as realized by Peter Gülke. It is an abomination at every level, and it is a scandal that Schubert’s name should be associated with this musical misadventure.

The music sounds nothing like Schubert. It sounds more like Vaughan Williams. Rather, it sounds like a high school composer’s bad imitation of Vaughan Williams. Actually, that’s not being fair to Vaughan Williams. Or high school composers. Or bad imitations.

Gülke wasn’t the only one to realize Schubert’s sketches for a late symphony in D Major; Brian Newbould also created a version, and that version was later revised by a certain Pierre Bartholomée. But the materials they were working from were fragmentary at best, mostly just a few melodic ideas with some bass lines filled in and the occasional working out of inner voices.

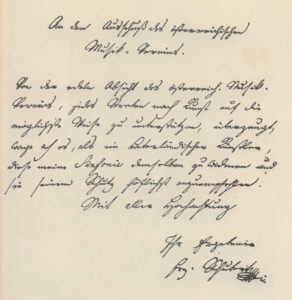

No surprise then that neither the harmonies, melodies, nor orchestration make any sense in the version I heard. The big lesson here is just how many iterations a piece – nay, a phrase, a motive, even a note – undergo on their way to becoming a completed work that’s representative of a composer’s style. Many composers have tried to hide the painstaking process behind their greatest works (see, for example, Johannes Brahms, who burned all his drafts) but even a Mozart doesn’t necessarily sound like Mozart at the first stages of a draft. Certainly a Gülke doesn’t sound like a Schubert.

But on top of that, there’s another, much more objective sense in which this piece can not be said to be Schubert’s 10th symphony: Schubert only wrote seven and a half symphonies in the first place.

You probably get what I mean by the ‘and a half part’ – the two movements that comprise Schubert’s ‘Unfinished’ Symphony. But, you protest, the ‘Unfinished’ is Schubert’s 8th, and the 9th is the well-known C Major symphony, so certainly he composed eight and a half symphonies at the very least.

If that be the case, ask yourself this: when’s the last time you heard Schubert’s 7th? Not ringing any bells? That’s because there is no such piece! Rather, one might say that any piece purporting to be Schubert’s 7th suffers from the same essential musical invalidity as does the so-called 10th: the piece only exists in sketches which have since been realized (also by Newbould.)

Actually it’s a little more complicated. When publishers were bringing out Schubert’s symphonies, they purposefully left the No. 7 spot blank, publishing the ‘Unfinished’ as No. 8 and the Great C Major as No. 9. Scholars had come across references to a symphony composed by Schubert that they believed to be lost (the so-called ‘Gastein Symphony’). They kept a spot open in the chronological numbering in the hopes of finding it.

It’s now generally agreed that the symphony referred to was in fact the Great C Major. Which, ironically, means that the musicologists did the right thing, since the Great C Major really should be Symphony No. 7 (if we’re only counting completed symphonies.)

To tidy up the rest of the mess, I’d propose (to… the world?) that the ‘Unfinished Symphony’ should just go by that description alone – no number at all.

But at the very least, if you’re going to keep performing this so-called 10th symphony (and by all means, please don’t) at least put Gülke’s name up front and bury Schubert’s deep in the program notes; it’s the least we can do.