I’m preparing to conduct Beethoven’s 9th (the last movement, anyway) and that’s brought me full circle in terms of my blogging, because in my very first blog post, I wrote about how obsessed I was with one particular marking in the score: “selon le caractère d’un Recitative mais, in tempo”. It’s a phrase so linguistically fluid it practically wipes right off the page, combining vocabulary, grammar, and spelling from French, Italian, and German, yet it would hardly raise an eyebrow from a properly trained classical musician anywhere in the world.

But now I’m obsessed with an even tinier detail of this score: the ‘y’ in the word “Elysium”. Y? Because we love you! And because I’ve got to figure out how the singers are going to pronounce it. People wonder what a conductor actually does. Well I’m here to tell you: she makes CHOICES honey.

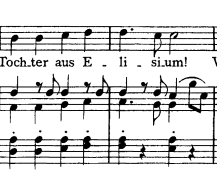

In Modern German ‘y’ is pronounced ‘ü’, so if you listen to the first 12 of the video below, you’ll hear it pronounced “Tochter aus Elüsium”:

But here’s the thing: I’m not convinced this letter should really be a ‘y’ at all. (mic drop)

See, as I prepared this piece, I marked up a choral score for my colleagues, and I noticed this:

Elisium! With an ‘i’! This I had never seen before in any edition of the score, but I was intrigued, because certainly a word spelled this way would properly be pronounced Eleesium, right?

Now I had two questions: 1) how did Schiller (the poem’s author) spell it, and 2) how did Beethoven spell it? Here’s the printed page from Schiller’s collected works of 1812, Beethoven’s likeliest source for the text:

And there, adorned in all it’s fraktural splendor, ‘Elisium’ is spelled with an ‘i’.

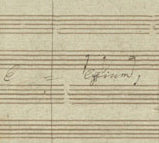

OK, but there’s still a discrepancy between the scores, so how in fact did Beethoven spell it? Well you can have a look at his original manuscript over at the Berlin State Library Archives, and if you can decipher his handwriting I think you’ll find there’s most definitely a ‘y’ in there:

So Schiller spelled it ‘Elisium’, Beethoven spelled it ‘Elysium’ but either way, how do you pronounce it? Well, if history be any judge, I’d say it’s pronounced the ee way (or [i] for you IPA folks out there.) Certainly this is the traditional approach—listen, for example, to Joseph Krips’ recording:

In hopes of some historiographic confirmation though, I navigated over to the German Wikipedia article on the letter ‘y’ and found this bombshell:

Noch im früheren 19. Jahrhundert war hingegen die Aussprache [i] üblich.

(“However, the pronunciation [i] was still commonly used in the beginning of the 19th century.”)

So we can be pretty confident that El[i]sium would have been the pronunciation in Beethoven’s time, so much so that ‘i’ and ‘y’ were interchangeable.

But what gives? In every edition of the poem published during Beethoven’s lifetime, the word was spelled ‘Elisium’. Whereby and wherefore did the composer come to make the alter the poet’s orthography?

This remains a total mystery to me and I welcome any insights or information. Maybe I should set up a toll free hotline. My best guess is that someone in Beethoven’s circle brought to his attention that, as a Greek loanword, ‘Elysium’ would more customarily be transliterated with a ‘y’, as the German were (and are) in the habit of doing.

But clearly Beethoven decided to change the ‘i’ to a ‘y’, so I’ll admit, I do have a lingering doubt—why would he bother to change the spelling if he didn’t intend any actual effect on the sound?

And an even better question: why is there nothing written about this anywhere?? Google was NO help. Shouldn’t someone have written, like, a 30,000 word musicology dissertation on this by now? Or wait, did I just do that? I guess this is more like 300.