Now we come to the vaguest of my Top 10 lists. As far as the qualities we’re looking for in a composer, this list has no more specificity to it than the original Top 10 Composers List what first inspired my project.

I like having this list be more open-ended though, because I think we’ll get a lot more interesting interpretations of what makes a good 20th/21st century composer and hopefully a lot of variety in musical style.

Obviously, music in the 20th century was a whole new ball game. First, there was this little thing called Sound Recording, which forever changed the ways in which music is created and disseminated. Then there wholly new channels of communication allowed us to out about all the tinkerers and oddballs, the hermits living in caves and railroad cars (not to mention the suburbs of Mexico city.) Supposedly at some point along the way, innovation trumped beauty as an aesthetic value in its own right.

OK now, before playing/judging, take a careful look at the title of this list: we’re not looking for composers who WORKED after 1900, we’re looking for composers who were BORN after 1900 (or during that year – so Copland is fair game; Poulenc is not.) It’s just another little tweak to make the game harder/more interesting. Maybe.

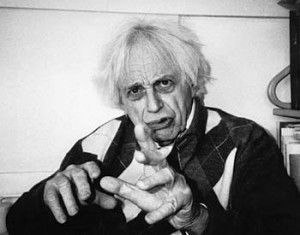

1. Gy̦rgy Ligeti (1923 Р2006)

György Ligeti. The Ligster. “El Ligerino” (if you’re not into the whole brevity thing). I think Ligeti is the best of what the 20th century is all about: he was a bold experimenter, he was a meticulous technician, and he forced musicians to reckon with the extremes of difficulty presented in his writing.

Ligeti’s music also forces listeners to confront their conceptions about what music IS (Poème Symphonique), yet it retains an obvious connection to the great music that came before him. He was part of several movements: Dada, Darmstadt, even “World Music” to a certain extent, but he was beholden to none of them.

His music is intelligent but not abstruse. He lived through some of the 20th century’s greatest atrocities (he even escaped a forced labor camp in Hungary) and yet he had a wicked sense of humor (his only work to bear a published opus number lists it as “No. 69”.) He lived and created in the tiny sphere of the European avant-garde, and yet his music became a part of pop culture.

I think this about sums it up:

(Nonsense Madrigals, The King’s Singers)

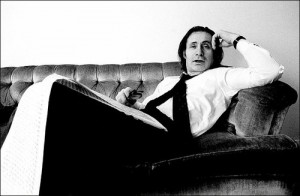

2. Alfred Schnittke (1934 – 1998)

Why do I love Alfred Schnittke so very, very much? There’s obviously the surface layer – the way that he can write a beautiful piece of music, then manipulate it 100 different ways. But that would be worth nothing if there weren’t a tremendous and powerful meaning behind it.

Schnittke was in every way a more subversive artist than his Russian forbears, Dmitri Shostakovich and Sergei Prokofiev. Admittedly, this was a much easier task for a Soviet artist working after the death of Stalin. But I think it says a lot about Schnittke that even after all the walls had fallen, when the great 2nd World had come to its knees, he could have used his enduring popularity (and yes, he is a national HERO in Russia) to forge a new, and undoubtedly lucrative career by playing ball with the new regime; instead, he refused the Lenin Prize and moved to Germany.

Schnittke was the first composer to make full use of historical styles as a means of musical story-telling. He was also the best. His creepy distortions of earlier musics suggest a commentary about the meaning an manipulation of truth – let’s not forget that during the Soviet era, subscribers to the Soviet Encyclopedia would routinely receive replacement pages to be glued into their volumes when certain artists and politicians had become “non-persons”.

(Concerto Grosso No. 1, Kremer/von Dohnanyi)

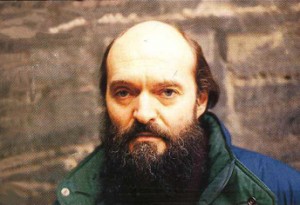

3. Arvo Pärt (1935 – )

The Estonian composer Arvo Pärt is considered the great mystical figure of contemporary music. There’s something of an irony involved here: he’s well published, well recorded, well represented in the media (especially in film soundtracks), well studied by the academic establishment, and even a frequent interview subject.

But despite our access to the man and his music, there’s no denying the powerful sense of the mystic in his art. Pärt famously invented a system of writing counterpoint called tintinnabulation which mimics the ringing of bells. His melodies recall Gregorian chant. Amazingly though, his music doesn’t sound like an anachronism – it sounds like an eternity.

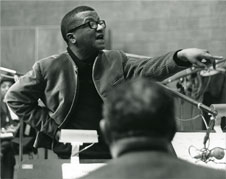

4. Billy Strayhorn (1915 – 1967)

If you read David Hajdu’s Strayhorn biography Lush Life (and I certainly recommend that you do), you’ll find out just how very difficult it is to separate the contributions of this jazz legend from those of his constant collaborator, Duke Ellington. But Ellington was born in the 19th century, so that makes it easy to choose Strayhorn for this list.

If you read David Hajdu’s Strayhorn biography Lush Life (and I certainly recommend that you do), you’ll find out just how very difficult it is to separate the contributions of this jazz legend from those of his constant collaborator, Duke Ellington. But Ellington was born in the 19th century, so that makes it easy to choose Strayhorn for this list.

As best I can tell, Ellington was the revolutionary, Strayhorn the poet. Ellington was nearly two decades Strayhorn’s senior, and while young Billy was still knee-high to a grasshopper, Duke was creating major innovations in harmony, form, and especially orchestration that would change the face of jazz composition.

But at the tender young age of 16, Strayhorn famously penned the aching and harmonically sophisticated ballad “Lush Life”. During the very same period, there was this little gem, a melancholy ode to Chopin entitled “Valse”:

5. Steve Reich (1936 – )

I’m not sure why, but I somehow feel like Steve Reich is a better minimalist than a composer. It’s probably silly to even talk about such things, but I’d be interested in hearing if anyone else knows where I’m coming from.

I’m not sure why, but I somehow feel like Steve Reich is a better minimalist than a composer. It’s probably silly to even talk about such things, but I’d be interested in hearing if anyone else knows where I’m coming from.

His early pieces were tremendously innovative and they gave life to a whole new musical world. Sometimes they shimmer, sometimes they startle. Some can be preformed by just about anyone (“Clapping Music”), others require unerring virtuosity (“Piano Phase”).

Maybe it’s just me, but I find Reich’s newer work much less fresh and less skillful. But maybe it’s just that his music has infiltrated the entire musical panorama so thoroughly that I approach these more recent pieces with an unfair set of expectations.

But hey, good luck making funner music than this:

(18)

6. Stephen Sondheim (1930 – )

Allow me to expand on the things I said about Sondheim last time. First, he loves many of the same composers that I do: he’s frequently listed his favorites as Ravel, Berg, and Rachmaninoff. Not to mention Bernard Herrmann.

So he takes those composers, mixes them with some more from the Great American Songbook (esp. Harold Arlen and George Gershwin), folds in the most brilliant lyrics in Broadway history, and voilà , you have a soufflé:

(Who knew “Little Red Riding Hood” could be so creepy and so funny when you set it to a mixture of Ravelian blues and meta-Music Hall strolling music?)

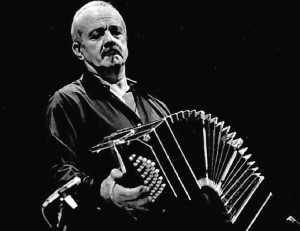

7. Ãstor Piazzolla (1921 – 1992)

The great innovator of the Argentinian Tango, Ãstor Piazzolla studied composition with the mythical French pedagogue Nadia Boulanger. Piazzolla’s music is infused with the language of Bach and the early 20th century European modernists.

The great innovator of the Argentinian Tango, Ãstor Piazzolla studied composition with the mythical French pedagogue Nadia Boulanger. Piazzolla’s music is infused with the language of Bach and the early 20th century European modernists.

I liken his music to Haydn’s or Johann Strauss Jr.’s: his pieces aren’t written for the dance, they are written to tell the story of the dance. Each piece is a miniature scene – the cabarets and night clubs where he cut his chops are the setting.

8. Thomas Ad̬s (1971 Р)

Thomas Adès is the real deal: a composer who writes music that is both interesting and emotional, has the piano chops to back up his incredibly demanding instrumental ideas, and makes a living off writing and presenting his own works.

Thomas Adès is the real deal: a composer who writes music that is both interesting and emotional, has the piano chops to back up his incredibly demanding instrumental ideas, and makes a living off writing and presenting his own works.

Add to that the fact that he’s adept at incorporating a variety of styles into his music and a natural flare for the dramatic (see The Tempest and Powder Her Face) and you’ve got a first rate composer.

(Violin Concerto, Marwood, COE/Adès)

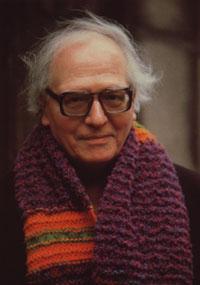

9. Olivier Messiaen (1908 – 1992)

Messiaen reminds me of two other composers on this list: Arvo Pärt, because of his fervent and mystical religious beliefs; and Ligeti because of their shared experience as prisoners during WWII (Ligeti had it much harder) and because they both wrote music that explores new ground while maintaining a direct connection to the romantic tradition (Messiaen’s is stronger).

Messiaen reminds me of two other composers on this list: Arvo Pärt, because of his fervent and mystical religious beliefs; and Ligeti because of their shared experience as prisoners during WWII (Ligeti had it much harder) and because they both wrote music that explores new ground while maintaining a direct connection to the romantic tradition (Messiaen’s is stronger).

But now that I think of it, there are more parallels: like Ligeti, Messiaen dabbled in various –isms throughout the 20th century and took only what he liked. Messiaen’s modal harmonies are often bear a passing similarity to Billy Strayhorn’s mellow sonorities.

Then there were all those damned birds. And the weird early electronic instruments. Let no one say that Messiaen wasn’t an original.

(Turangalîla Symphony, RCO/Chailly)

10. Alberto Iglesias (1955 – )

It would be slightly insane to make a list of the “Top” composers born after 1900 and not include at least one person who primarily worked in the essential 20th century art form, film. Probably a lot of you will think it’s equally crazy to choose Alberto Iglesias, a semi-obscure Spaniard who’s only scored about 20 movies, to fit that bill.

My reasons: Iglesias takes the best things from other composers who rank among my favorites: Herrmann, Max Steiner, Miklos Rózsa – even Danny Elfman. Then he turns the volume up. He is an amazing orchestrator and user of instruments more generally. Much like Pedro Almodóvar, his primary collaborator, Iglesias speaks an altogether contemporary language but informs it with a thorough knowledge of history. Both gentlemen speak to our lightest and our profoundest selves.

Discuss

Formulating this list was a lot harder than I thought it would be. It shouldn’t have come as any surprise that an instruction like “Pick the top 10 composers” would leave me adrift though. The good thing was that in choosing the contenders, I was able to better define my criteria.

I’m glad I used a fixed birth date as a criterion: for one thing, it made things easier than if I had gone with an even vaguer notion of “20th/21st century” composers, because then there would have been invited all this blabbing about who’s secretly a 19th century composer, etc. Choosing 1900 as a starting point for composer births was arbitrary enough.

I ended up going for a bon milieu approach: I preferred composers who were not afraid to experiment but who didn’t specifically align themselves with any group, and who made music that was both daring and beautiful. Not really any different then the criteria I would use for composers of any era.

Now, my conversants, to the comments section. The usual rules apply: make your own top 10 list or modify mine by replacing my selections with you own. There’s a whole lot of latitude in this list – much room to interpret that pesky word “Top” and bring in a lot of different ideas about music. Also, for this list please mention at least the birth year of your submissions.