People often ask me what the “C.” stands for in “William C. White.” They usually guess Charles or Christopher or Connor, but what it actually stands for is Coleman.

I got the name from my father, Coleman Livingston White, Jr., who, naturally, got it from his father. As a child, I wished I had been named Coleman Livingston White III. I thought it sounded fancy and English, and fanciness and Englishness are two things of which I’m rather fond.

Beyond my grandfather’s generation, I knew nothing more of the name “Coleman Livingston†— it was just an axiom of my paternal heritage. Other than that they hailed from South Carolina, I knew little of the history of that side of the family. I never so much as thought to wonder where the name had come from until I was in my late 20s. Let’s put a pin in that for now.

✥

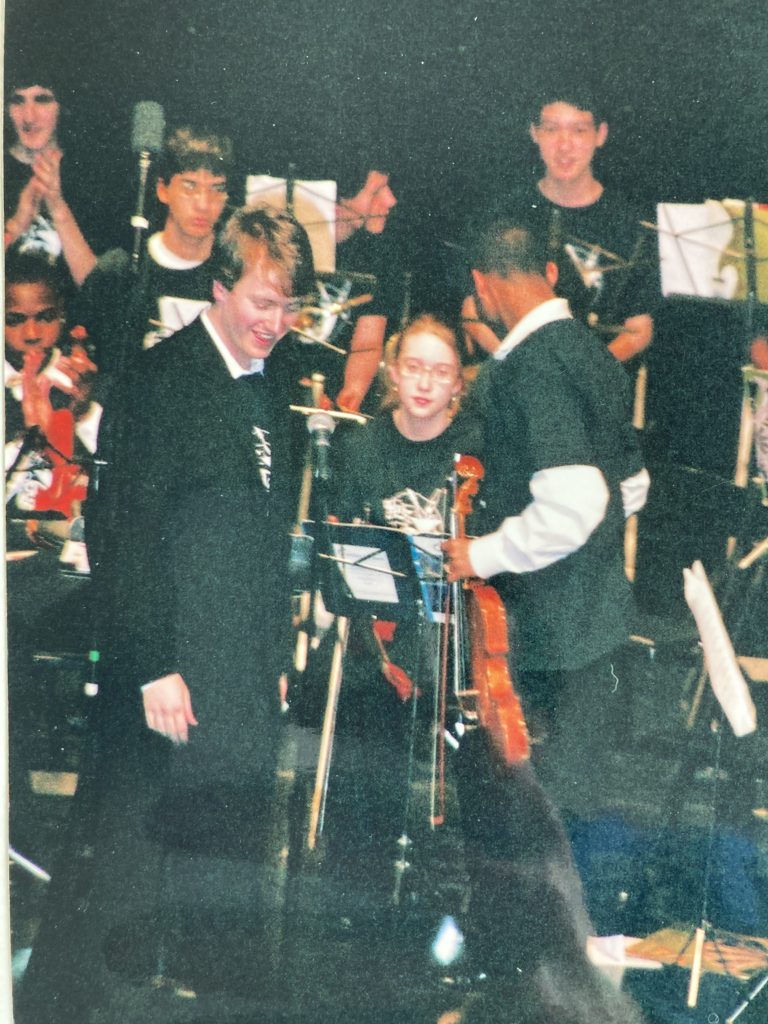

The first job I had after graduating college in 2005 was as music director of the Hyde Park Youth Symphony, a small community music program on the south side of Chicago near the U of C, where I had gone to school. I was with those kids for three years, a period that was probably more formative for me than it was for them.

That orchestra was truly as diverse a group as you’re likely to find anywhere. There were rich kids and poor kids, black, white, Asian, and Latino, and, crucially, every possible permutation of economic circumstance and ethnicity. They ranged in age widely, as tiny youth orchestra programs tend to. It was a little musical one-room schoolhouse.

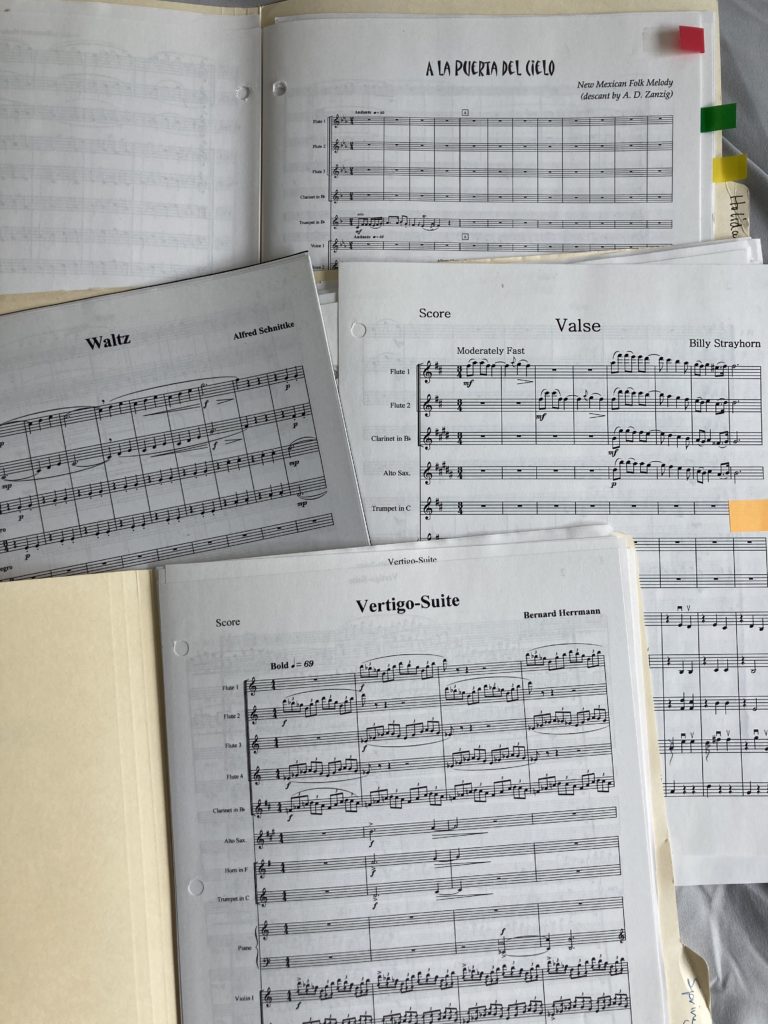

It was a ragtag assemblage of instruments. One year we might have 5 flutes, 4 clarinets, a saxophone and a trombone, the next year might be 3 oboes, percussion, and piano. We took the kids because they wanted musical instruction, not because they were highly accomplished players or they formed a coherent “symphony orchestra.” This meant that I had to arrange and orchestrate every single piece we played, both for their skill level and for the instrumentation we had available.

As you can imagine, this was excellent training for me as a composer, but crucially, it gave me total freedom in programming. Yes, I was chained to my desk for hours upon hours drawing up Finale scores, but the truth was that since I was writing all the music myself, I could program anything I wanted to.

So left to my own devices what did we play? Among classics by Corelli, Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven, we played “The Advantages of Floating in the Middle of the Sea†by Stephen Sondheim, a selection of waltzes by Alfred Schnittke, the Vertigo Suite by Bernard Herrmann, a scene from Les Parapluies de Cherbourg, and the Chopinesque “Valse†by Billy Strayhorn. My tastes may have expanded since then, but they certainly have not changed.

✥

Every year, our major concert took place at the DuSable Museum of African American History, and the program naturally featured music by African American composers. Certainly the greatest height we achieved at in the museum programs was premiering an orchestral work composed by one of the students, a wide-ranging young man who not only wrote this tone poem but created a comic book to illustrate it.

Another project from the DuSable museum that I’ll never forget though, is a concert of selections from Scott Joplin’s opera Treemonisha.

Treemonisha comes from the year 1911 and combines strains of ragtime, light opera (aka G&S), and even Wagner. The story concerns a community of ex-slaves in Arkansas near the Red River. It was all but unknown until the 1970s when it was resurrected by Katherine Dunham and Robert Shaw.

Treemonisha was the second opera composed by Scott Joplin. The first, A Guest of Honor, has been lost, but it is supposed to have memorialized the 1901 visit of Booker T. Washington to the White House. We’ll likely never know the exact contents of A Guest of Honor, but given that the libretto Joplin wrote for Treemonisha was very much in line with Booker T. Washington’s outlook, we can assume it was a sympathetic and laudatory portrayal.

Alas, Joplin’s was not the only artistic response to that dinner. Booker T. Washington’s White House dinner caused a considerable backlash among white southerners, memorialized in an anonymous poem that was printed in several newspapers called “Niggers in the White Houseâ€.

You can click on that Wikipedia link and read the poem, and maybe you should, but if you don’t want to, just take it from me that it’s every bit as vile as you’d suspect.

The great tragedy is that whereas A Guest of Honor was lost to time, “NitWH†kept cropping back up. In 1929 it resurfaced when Lou Hoover, the first lady, invited Jessie De Priest to a White House tea for congressional wives. Jessie’s husband Oscar Stanton De Priest was the first African-American to be elected to congress since the days of reconstruction, and the first ever from a northern state. He represented Illinois’ 1st congressional district, which is in the south side of Chicago. It includes Hyde Park.

This time the poem wasn’t just printed in the papers. It was read on the floor of the senate. The senator who read it represented the state of South Carolina. His name was Coleman Livingston Blease.

Before he was a senator, Blease had served as governor of South Carolina in the first years of the 20th century. His unadulterated brand of white supremacy was so popular with poor white South Carolina mill workers that many of his constituents named their children after him. It’s what my great-grandfather did.

✥

Black history is American history, and it touches us all no matter what our race may be. I’m lucky that my parents raised me in an explicitly anti-racist manner, but we’re not only raised by our parents — we’re also raised by ghosts.

Black history matters. Black kids matter. Black parents matter. Black teachers matter. Black communities matter. Black art matters. Black music matters. Black lives matter.