I don’t believe there is such a thing as a Good Melody. I almost don’t know what such a thing would mean, because for me, a melody is nothing without a good harmony. Or perhaps I should say, “harmonic progression.” Harmony’s great, but what’s the use of a good harmony without a beautiful melody to glide upon it, to argue against it, to define it, to sing it?

So when people speak of “the Great Melodists,” I think they’re really talking about those people who are masters of uniting beautiful melodies with complimentary harmonies, not just writing tunes. Gregorian chant, which may be considered the purist form of melody, interests me on little more than an intellectual level and rarely moves me beyond a vague sense of the ethereal. There are even certain bel canto opera composers from the 19th c. who wrote grand melodies with attractive features, but who won’t be included on this list in favor of composers who wrote melodies at least as good, and had more interesting harmonies.

The most basic of melodies can be rendered voluptuous when wrapped in a cloak of warm harmonies. Here’s my list of the people who did it best, the third such list in our series. See if you agree.

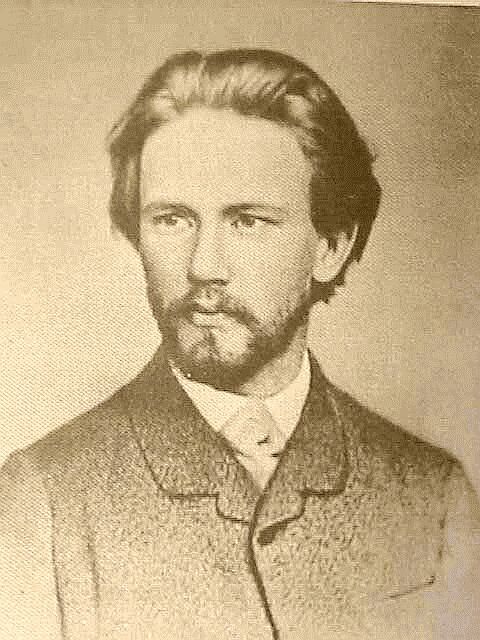

1. Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840 – 1893)

When you think Tchaikovsky, you think melody. [Of course, really, you think harmonic melody, but I’ll try not to keep dwelling on this point too much.] Tchaikovsky’s melodies are gorgeous, voluptuous, songful things. There are big, sweeping melodies that take center stage. There are also small little melodic fragments that, for some reason, have as much power as most other composers’ biggest tunes. It takes a brave composer to suffuse every bar with melody this way – wouldn’t you be worried about running out?

2. Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873 – 1943)

You might notice a Russian theme (thème Russe?) developing here. Those Russians sure can write some harmonic melodies. Rachmaninoff adored Tchaikovsky, and it shows. His harmonies are bolder and often darker than his model’s though, and his melodies contain many more surprises.

A lot of people think that beautiful melodies simply spin out from their creators’ hearts. But a great tune is equal parts intellect and emotion. This melody, from Rachmaninoff’s 2nd piano concerto, could end any number of places and be perfectly satisfactory, but through a series of ever more ingenious harmonic tricks, Rachmaninoff keeps this one melodic thread going for over a minute. It rises and falls many times, but it has only one apex point — one note that is the top of the melody’s arc. And, not surprisingly, this is the note with the most color to the harmony, the most poignancy and beauty. Just listen – you’ll hear it about 48 seconds in.

(Piano Concerto #2, Atzmon/NPO, Frühbeck de Burgos)

3. Giacomo Puccini (1858 – 1924)

Puccini is such an obvious choice because of his lush operatic melodies. And he brings us to another point about the great harmonic melodists, which is that they tend to be loved by the public but disparaged among the musical intelligentsia. What a mistake is made in the groves of academe when the craggier professor types assume that a popular touch comes at the expense of a composer’s craft. At least in Puccini’s case, it’s very much the opposite. He was a genius of harmony, color, and orchestration (much like Rachmaninoff and Tchaikovsky, btw.)

I think it would take a real cold fish not to get a body high from a passage like this:

4. Richard Rodgers (1902 – 1979)

Of all Broadway’s great composers, Richard Rodgers is the most distinguished melodist. He’s also an excellent example of what this particular list is really about, namely, who could write the best musical material. Beethoven’s melodies can be transcendent at times, but he’s hardly our most accomplished tunesmith. Beethoven’s great strength is the way he used his material. Rodgers, on the other hand, only wrote melodies and harmonies – he didn’t arrange, orchestrate, or write the lyrics for any of his tunes. [Though he certainly benefited from collaborating with one of the most brilliant colorists in the history of Broadway orchestration.]

So I think it’s a real testament to his talents that the melodies themselves are the most distinguished feature of his musicals. Sure, Oklahoma was a landmark in music theater history for its bold exploration of form and artistic integration, but it’s a melody like this that brings tears to your eyes:

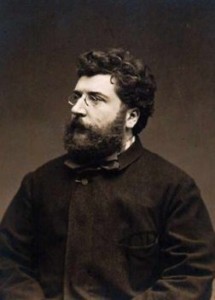

5. Georges Bizet (1838 – 1875)

Not surprisingly, we come to another composer most well-known for his work in the theater. Carmen might be the greatest collection of tunes in opera. Note the distinction — not the greatest opera (though it sure ain’t shabby!), but the best set of tunes as an opera.

Not surprisingly, we come to another composer most well-known for his work in the theater. Carmen might be the greatest collection of tunes in opera. Note the distinction — not the greatest opera (though it sure ain’t shabby!), but the best set of tunes as an opera.

Interestingly, Bizet was a mightily accomplished piano virtuoso, even impressing Liszt at a dinner party with his chops. [You know, his playing. Not his lamb chops -—or his mutton chops, impressive as they may have been.]

Prepare for aural ravishment:

(“L’Arlesienne Suite”, Ulster/Tortelier)

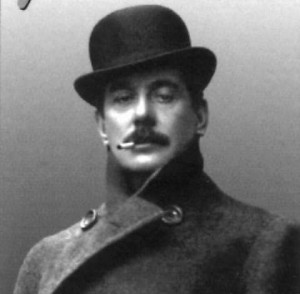

6. Alexander Borodin (1833 – 1887)

The third Russian on our list, Mr. Borodin’s primary vocation was as a chemist (a rather dour chemist, from the look of it). For those who care about such things (or for those who just don’t have time to read the entire Wikipedia article), Mr. Borodin discovered the Hunsdiecker Reaction 90 years before Hunsdiecker. And Hunsdiecker didn’t even write a single quartet. Asshole.

The third Russian on our list, Mr. Borodin’s primary vocation was as a chemist (a rather dour chemist, from the look of it). For those who care about such things (or for those who just don’t have time to read the entire Wikipedia article), Mr. Borodin discovered the Hunsdiecker Reaction 90 years before Hunsdiecker. And Hunsdiecker didn’t even write a single quartet. Asshole.

Borodin’s tunes are so lovely that they famously made it to Broadway. He sure knew his chemistry, all right. No wonder he’s so beloved:

7. Franz Schubert (1797 – 1828)

Of the so-called “Vienna Four“, Schubert is the tuneliest. He may also be the ugliest, but we’ll save that discussion for a later list. Mozart tended to make his singers his instruments; Schubert made instrumentalists into singers.

Of the so-called “Vienna Four“, Schubert is the tuneliest. He may also be the ugliest, but we’ll save that discussion for a later list. Mozart tended to make his singers his instruments; Schubert made instrumentalists into singers.

Schubert also produced a stunning variety of melodies. The music of his late masses spins out into eternity, wrapping us in transcendence. A tune like “The Trout” is as solid and rustic as an Austrian lumberjack. But he could also write a gasping little noir melody like this one, which takes place entirely within one person’s soul:

8. Giuseppe Verdi (1813 – 1901)

There is some very basic thing that doesn’t sit right with me about Verdi. But then I go to one of his operas, I do my best to inhabit his world of dramatic pacing, and the majesty and melodrama of his music win me over. Then I leave, and I sort of half-embrace him. And the cycle repeats itself.

There is some very basic thing that doesn’t sit right with me about Verdi. But then I go to one of his operas, I do my best to inhabit his world of dramatic pacing, and the majesty and melodrama of his music win me over. Then I leave, and I sort of half-embrace him. And the cycle repeats itself.

Was Verdi really a greater writer of melodies than his immediate predecessors, the bel cantists? That is really, REALLY hard to say, because they were all pretty damn good.

(La Traviata, Gheorghiu/Solti)

9. Henry Purcell (1659 – 1695)

I swear I’m not putting Purcell on here just to be weird or contrarian or whatever, but I will admit that I find his music incredibly unique, and that you’re very likely to see him on my “Personal Favorites” list. Part of the reason he’s getting on this list when all the other composers are 19th century or later is that he lived at this weird historical period when Tonal Harmony was not quite standardized, but it sort of worked, and I think this allowed him to use harmony in a way that I don’t hear from any other composer.

I swear I’m not putting Purcell on here just to be weird or contrarian or whatever, but I will admit that I find his music incredibly unique, and that you’re very likely to see him on my “Personal Favorites” list. Part of the reason he’s getting on this list when all the other composers are 19th century or later is that he lived at this weird historical period when Tonal Harmony was not quite standardized, but it sort of worked, and I think this allowed him to use harmony in a way that I don’t hear from any other composer.

I also think that he’s the only “classical” composer to write idiomatically for the English language, and he did it in a tuneful way that we wouldn’t see again until 20th century popular music came. Although that’s sort of complicated because a lot of his music sounds like what I’ve always guessed to be the pop music of his era.

(“If Music be the Food of Love”, King’s Consort)

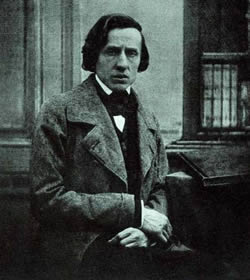

10. Frédéric Chopin (1810 – 1849)

Not being a classically trained pianist, Chopin will always remain something of a mystery to me. But again, he’s sort of like Verdi in my personal pantheon — I don’t think about him much, but when I’m listening to his music, I can’t resist its allure… until I start to get bored.

Part of the genius of Chopin’s melodic writing is that he took full advantage of his medium, the piano – when writing for the human voice, the range of a melody is much more restricted. I’m not easily won over by lots of fancy figuration — Chopin’s pianistic coluratura, if you will. But there are those times when Freddy gets out of his own way and presents his melodies in their gorgeous simplicity. I include him here because I think he had a wonderfully colorful harmonic palette, something that his great heroes of the bel canto often lacked.

(Eb Nocturne Op. 9, No. 2, Rubinstein)

Discuss

We’ve had some stirring commentary in the past few, so let’s keep it going. Tell your friends! I’ve already learned a ton from your collective knowledge.

In a lot of ways, this was my favorite list to make [because it sounds so preeetty]. I really hope we get some bel canto queens up in here talkin’ bout Gaetano Donizetti or some shit. And since we have no genre guidelines, I think this list more than any so far should bring up a lot of debate and new names.

Remember the rules of the game: either put up your own top 10 list; or, if you’d prefer to suggest an alternative to one of my composers, you must choose a composer to remove from my list. So let’s see how fast everyone can type “Purcell” and click submit.

Someone has to be shocked that Dvořák didn’t make the list, right? I’ll switch out Bizet for the extremely well-thought-out argument that I find Bizet a little boring.

Alyssa –

I thought a lot about Anton D. and his compatriots. I find the Czech to be a very melodious people in general. As much as I hate “The Moldau” and everything it stands for, it’s a hell of a tune.

Question: do you necessarily think that Dvorak is a better melodist than Brahms? I think so, but I gave them both serious consideration.

Will,

An interesting question, especially because we’re considering “harmonic melodists”. Didn’t Brahms find the voice leading under Dvořák’s melodies a little haphazard? If Brahms was right, maybe that’s why Dvořák’s melodies seem so raw and heart wrenching. On the other hand, perhaps Dvořák was a little more innovative than Brahms gave him credit for.

Maybe I’m quick to say Dvořák, because Brahms is in the running for so many other lists. But I have a hard time trading some moments in the Requiem, 7th and 8th symphonies, and even that famous Rusalka aria for anything Brahms wrote.

I’ve been really excited to see what you came up with for this list and I must admit that I find it…conservative. Sort of. Not that I’m disappointed; it’s just really interesting how you interpreted your own definition which seems to lead towards the self-acknowledged bias towards the late 19th century (and Russia).

That said, I came up with three names not on your list: Faure, Monteverdi, and Brahms. Faure, to me, needs no explanation for inclusion on this list. I mean, the man was fearless when it came to harmony and you simply cannot divorce his melodies from their support. And yet, if you do, they still hold their own, but the difference in the effect is staggering.

Monteverdi is maybe my loosest application of the definition. Be it Orfeo or the Fifth Book of Madrigals, it’s often hard to find a bona fide melody in the normal sense of the word, but there’s no denying a very strong sense of drama, forward motion, and emotional content in his harmonic world. I mean, Orfeo is totally driven by his über-awesome harmony, but it’s the sung recitative we really pay attention to. It’s an interesting symbiosis, but one that Purcell has some things in common with (and I absolutely agree that he should be on the list).

And Brahms. I think the above Dvorak vs. Brahms discussion is fascinating. I, too, considered both of them and it sort of makes me sad to have to choose (not that I have to, I suppose, but since I’ve decided to fit these cats into Will’s list, I thought I’d make life easier by limiting myself. Oy). I guess for me the issue is one of harmonic vocabulary. I have no real evidence for this, but I imagine that if you compiled a Harmonic Lexicon for the two composers in question, Brahms’s would be significantly thicker. Dvorak might win as an orchestrator (nobody should take this statement too seriously…please (I’m not sure I believe it)) but Brahms throws chords and counterpoint in your face from NOWHERE and with such a profound sophistication. Whenever I think about writing choral music, I consult the second entrance of the choir in the first movement of the requiem (m. 19 for all the nerds), which I consider to be the BEST bit of choral writing EVER. And it’s all about the interaction of melody, counterpoint, timbre, and harmony. So, yeah.

Now the tricky bit. I choose to vote off Bizet (good melodies, yes, but I think my dudes have way more awesome harmonies), Verdi (ditto…though this also hurts me a little), and…um…I guess Chopin vs. Faure is the issue (again, sad) – I love Tchaik, Schubert (duh), and Borodin being on the list, I have been convinced about Rogers and Puccini, and Rachmaninoff…well, maybe it’s more like Faure vs. (Rachmaninoff+Chopin). Your argument for Sergei makes sense and is basically indisputable, and Chopin is perfectly harmonically adventurous, but, each in their own way, are kinda “Faure Lite,” ya know?

Also – I thought a lot about Berg and Beethoven. Just puttin’ that out there.

Alright, so, here was some of my reasoning about the above considered gentlemen:

Brahms: Yes, striking, gorgeous melodies abound in his music. But for the sake of this list, I would pick Dvorak over Brahms. Why? Because for me, Brahms’ melodies are so very intertwined into the fabric of his gesamtmusikwerk. Not only are they connected to the counterpoint, but they are so dependent on and integral to the towering structures of his works that its almost hard to parse them out. To be sure, there are some beautiful long line melodies (I’m thinking particularly of the second themes of the first movements of his 2nd and 4th symphonies), but even those tend to MELT into the textures – which is AMAZING that he could do that, but anyway.

Faure: another excellent choice, and I agree with everything you said. My opinion of Faure has always been that he’s the best composer at writing sad music. Not tragic, not wailing, but just that plain sort of sadness that happens inside your body. And I think that’s very, very hard to do, and I give him major props for that. And yes, dude wrote some hella good tunes.

Monteverdi: I like Monteverdi and all, but this is too much of a stretch for me.

Gabe: I am shocked that you did not mention Mozart. Shocked. Actually, I basically assumed that there would be like 10 responses substituting Mozart for Purcell as soon as I clicked “Publish” on this list. The reason I didn’t include him is that, gorgeous and perfect as his melodies may be, they are often a bit formal for my taste.

I know it’s like, passé or whatever to say that Beethoven didn’t write good melodies (and that Schumann couldn’t orchestrate and that Sibelius couldn’t walk a straight line) but seriously Gabe, Beethoven?

Well, here’s the dilly-o (dilly-yo? deallyo?): I’m taking your position on the primacy of harmony very seriously. If I understand your contention correctly, it implies that you can have a total shit melody but when wrapped in a compelling harmonic blanket, shit it remains no longer. Thus, consider the beginning of Beethoven’s fourth concerto: gorgeous and memorable…because of the harmony and in spite of the simplicity of the tune. Likewise for the second theme of the Waldstein (a scale!!?), the last of the Diabelli variations, etc.

It was precisely this line of reasoning/priorities that led me to propose Monteverdi and Faure, who, most certainly did more than just sad well (for shame, sir) while at the same time excluding Mozart. Lord knows I’d put Mozart on every one of these lists if I allowed myself the privilege of raw and impulsive responding, but I’m trying to be unbiased. (BTW – Happy day after Mozart’s 255th birthday!) Personally, I don’t find his melodies to be particularly conservative (K. 550, the Kyrie fugue from the Requiem, Ach ich fuhls from Zauberlote, that weird little Gigue…I could go on), but I feel like they really work with the harmony in concert. I mean, that’s true of all the stuff we’re talking about, but I’d say that in Mozart’s world, the effect is a holistic once that draws attention not simply to melody and harmony, but also rhythm, timbre, counterpoint, etc., and all at the same time and in relateable proportions. I mean, how often in Mozart is it impossible to say when exactly a melody starts or ends? Really often. That’s how often. So, in short, he’s the Man, ergo boss at everything.

Fantastic post! Wish I’d seen it sooner. I’m thrilled to see Purcell here, but the most glaring oversights for me are two other ‘P’s; Poulenc & Prokofiev. (In fact, when you throw in Puccini, one starts to wonder if Pachelbel deserves consideration.) I’ve always thought of Poulenc and Schubert as the greatest melodists of all, although I suppose that might be because they’re each known so much for songs. Here’s a hastily assembled list; I could easily see finding a place for Mozart and Handel, but they get plenty of attention and regard. But I think the Top 5 stand out.

1. Schubert

2. Poulenc

3. Tchaikovsky

4. Prokofiev

5. Gershwin

6. Puccini

7. Purcell

8. Kern

9. Rachmaninoff

10. Bizet

Mr. Monroe,

An honor to have you among us – I should say that I have been a big fan for years, and many of your most excellent videos have graced my facebook wall (if not the pages of this blog, but I’m foggy on that – certainly they are in my youtube favs.)

I keep trying to figure out just where the place is for Poulenc among these pages, but honestly, I never pegged the guy as a great melodist – I always thought he was a little more like Beethoven – a genius of harmony, harmonic rhythm, and figuration. But with an endorsement like this one, I will listen to his music again with new ears.

Prokofiev is one I never would have thought of, even though I have always been really interested in his melodies. It’s funny, every time I conduct his music (and by some coincidence, I’ve done a fair amount of it) I always end up studying his melodies and his endless ingenuity in varying them. It takes forever to find all of his little intricacies, but it’s so worth it.

Kern and Gershwin are such excellent choices, both brilliant in this sphere. But really, better melody writers than Rodgers? I’m not convinced 🙂

I found myself thinking about this a lot as the day went on – for me, what separates my first five (Schubert, Poulenc, Tchaikovsky, Prokofiev, Gershwin) is that they seem to have a limitless supply of great tunes that are ready to pop out at any moment. Will already said that about Tchaikovsky, but I find it with the others as well. Poulenc’s 2-piano concerto is a good example. Prokofiev is often thought of first as being rhythmic, dissonant, and brilliant, but there are great tunes around every corner. Haunting, like beginning of 1st violin concerto, folksy like all over Peter & the Wolf, soaring and expansive in Romeo & Juliet, 5th symphony, etc. And almost always idiosyncratic in some way.

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Michael Monroe and Bucks County Piano, Gail Fischler. Gail Fischler said: RT @MMmusing: Who are your greatest melodists? http://bit.ly/fYGQtK My top 5: http://bit.ly/i7phPH […]

Oh, I think Poulenc is much more of a melodist than Beethoven. He can certainly turn out gorgeously classical, Mozartian tunes like this; or spin out a Bachian figure into a lovely tune like the opening of the Oboe Sonata.

But a song like Fleurs, while richly harmonic, also has a shape and line that is distinctive and exquisite. And I can’t think of anything Beethoven wrote that’s like C or Le chemins de l’amour.

The latter shows how easily Poulenc could have been a “Great American Songbook” type composer; speaking of which, Faure’s Dans Les Ruines d’Une Abbaye has always reminded me of something your guy, Rodgers, would write. (It also sounds kind of like “Matchmaker, make me a match.”!)

The day after I wrote here about Prokofiev, I heard a brass quintet (plus percussion) play the Lt. Kije suite, and was reminded again of how varied and appealing his tunes are. And they just pop up all over the place, like in the middle of the finale of the Piano Concerto #3. I think maybe the 2nd mvt of Violin Concerto #2 is my favorite – but there are dozens of choices.

Thanks for all those links – that was a great listening journey, and you make an excellent case for M. Poulenc.

I’m covering a concert w/ Myaskovsky’s 22nd Symphony on it this week. Dude is a serious list-worthy contender in the melody arena.