I just finished reading Orhan Pamuk‘s 1998 novel My Name is Red, a superlative piece of literature set in late 16th century Istanbul concerning a murderous group of Ottoman miniaturists. Pamuk interweaves his brilliantly constructed murder mystery with extensive discussions of art, style and apprenticeship. I found this quote particularly interesting:

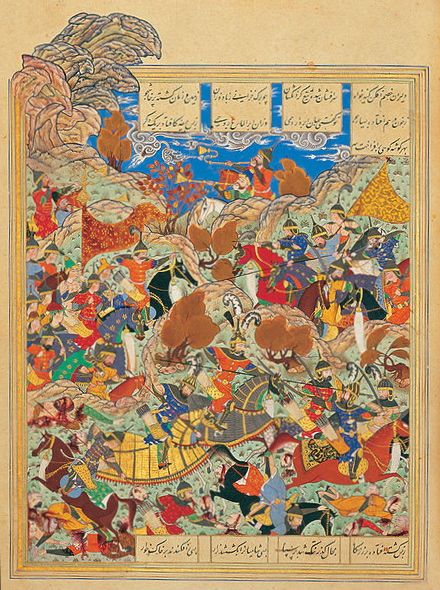

“Nothing is pure,” said Enishte Effendi. “In the realm of book arts, whenever a masterpiece is made, whenever a splendid picture makes my eyes water out of joy and causes a chill to run down my spine, I can be certain of the following: Two styles heretofore never brought together have come together to create something new and wondrous. We owe Bihzad and the splendor of Persian painting [above] to the meeting of an Arabic illustrating sensibility and Mongol-Chinese painting. Shah Tahmasp’s best paintings marry Persian style with Turkmen subtleties. Today, if men cannot adequately praise the book-arts workshops of Akbar Khan in Hindustan, it’s because he urged his miniaturists to adopt the styles of the Frankish masters. To God belongs the East and the West. May He protect us from the will of the pure and unadulterated.”

What a wonderful description of the relationship of artistry to craft – new art arises when someone masters craftsmanship in multiple styles and figures out ways of combining said styles to illuminate and enhance each other. I bring it up as part of my ongoing diatribe against those artists, musicians in particular, who seek to purge their work of all perceptible influences. A) good luck and B) it seems to me that in so doing all they end up with is a bunch of voiceless muck.

I know that this was a trend in many artistic spheres, but as far as I can tell, this blight – that is, the aesthetic wherein novelty was prized over artistry – seemed to have hit Music (i.e. Western Academic Art Music) worse than other disciplines in the 20th century. But I am continually heartened that this generation of, shall we say, “classically trained” composers takes music quite seriously and realizes that we are competing with popular genres (whose musicians are increasingly devoted to music as art), with other artistic media, and with the larger world of entertainment. [Ed: I think that competition among musicians is a wonderful, healthy thing.]

It is in this regard, and many others, that I would like to offer my highest praise for Timothy Andres‘ new album, Shy and Mighty, released by Nonesuch. I bought it just a couple of days ago and have been glued to my speakers ever since. What a debut album! This is really an album, both in the classical sense and in the contemporary sense of a recorded-album-cum-artistic-work, consisting of ten single movement pieces. I hesitate to call them miniatures – most of them are quite substantial pieces, with only two serving as brief interludes, but even these are part of a larger framework. This is really first-rate writing, and what’s more, it is a brilliant melding of influences as diverse as Steve Reich, John Adams, Olivier Messiaen, Dave Brubeck, Aaron Copland, Claude Debussy and a coterie of popular artists (“Out of Shape” really sounds like a pop song). To my ears, one of the strongest influences is Stravinsky’s Petrushka.

From a sort of dogmatic approach, one thing that I really admire about this work is that Mr. Andres speaks in his own voice and delivers a personal artistic message, but he never hides any of his influences. And yet, it’s not like they’re awkward or hovering on top of the writing or anything like that – rather, they’re beautifully interwoven. To me, his music proves my previous point: an individual voice is a product of taste, assiduously cultivated and ultimately refined. And to make things even better, in listening to this album (which I have done several times over the past couple days) one never stops to think about any of this – the influences move in and out organically – listener simply relinquishes himself to pure aural enjoyment.

Back to the opening idea of style, however, I often find myself wondering the job of uniting different styles is more difficult for composers today than in previous eras, for the obvious reason that there is a has been such a proliferation of musical styles in the past century. Not only that, but we now have access to recordings of all of these styles. It’s hard to say whether or not it’s harder or easier though.

Take Bach for example, who diligently learned and interpolated so many different stylistic strains in his music (look at any given Cello Suite for the range of nationalities and historical eras that informed his approach). From his youth through his maturity, Bach copied out manuscript after manuscript by hand so as to familiarize himself with the music of his forebears and contemporaries. He traveled incredibly long distances to meet musicians and learn their music. But was his job of rendering his discoveries into a new and unique voice more difficult than ours is today?

I haven’t the faintest clue, but I often wonder, because every time I compose a piece, it seems so difficult. The truth is probably that it’s always been incredibly difficult, but Bach was just such a master that he left no traces of its difficulty!