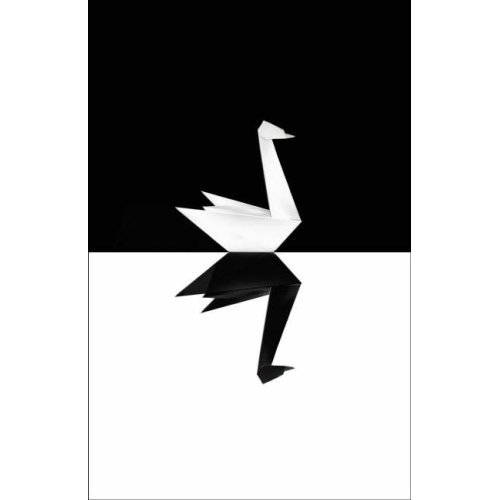

but you know “Black Swan”? It sucked. Donkey. I mean, you know, objectively.

What this film lacks is any sense of balance. Certain works of art are painful, and that’s very necessary and natural. But when a work is dark, it must, MUST have moments of joy and lightness in order to succeed. “Black Swan” starts in a dark place just gets darker and darker as it goes along.

Plus, how much clunkier can an exposition get? “You all know the story of Swan Lake…” but I’m going to tell it anyway. Vincent Cassel was quite decent in this movie, but the script he had to work with was abysmal. Same goes for Natalie Portman, though she did have the one really decent scene (calling her mother from the bathroom stall).

“Requiem for a Dream” was the same way, but even worse. “The Wrestler” I thought worked much better, and that’s certainly my favorite of Aronofsky’s films. That movie contained some redemptive moments. One actually understood the characters and their motivations. On the other hand, in “Black Swan”, Nina’s personal relationship with the Ballet is never made clear.

Plus, the details of backstage life were so laughably executed. OK, I’ve occasionally heard of ballet rehearsals with a violinist present, and if City Ballet wanted one, I’m sure they’d have him. The conductor was played by an actor, and that’s always the way of American films, and it’s really annoying. But why was the pianist on stage during the orchestral dress rehearsal? As a prop? And what about this: she gets measured for her costume THE DAY BEFORE OPENING NIGHT? I don’t think so…

The Tchaikovsky music was used rather basically. The way in which the composer, Clint Mansell extended the ballet score into the film’s main score actually made me laugh out loud on a number of occasions.

Overall, this movie went well beyond just being naïve and childish: it was terribly vulgar in my opinion. Egregious, and without any point. If a piece is meant to be painful, I’d like to be able to revel in the pain a bit – sort of like when you feel a canker sore with your tongue. This movie was more like amputating your own foot.

Let’s talk a bit more about scores though, shall we, because the score for The King’s Speech deserves mention in a particular context. First off, I thought this was an excellent movie, the apotheosis of a commercial period piece. And what a Period Piece it was. Not being a historian of 20th century Georgian London, I could hardly comment on the degree of accuracy rendered in this film’s art direction, but as a spectator, I certainly noticed the meticulous level of detail, and I was suitably impressed.

So why then, when the directors are clearly doing everything in their power to evoke a certain era, is it OK to have a score that bares not even the slightest resemblance to music from the period? Alexandre Desplat‘s score was fine, and very, very much in the mainstream film-scorey vein. But wouldn’t it have added that extra touch of authenticity to use some Vaughan Williamsian harmonies here and there? Perhaps a Waltonian melody? A bit of Elgaresque orchestration? Even an occasional boys choir or English hymn tune would have done.

[p.s., Memo to David Seidler: “I was Glad” referenced in the film’s script as “a hymn”, is not actually a hymn – it’s an anthem. An anthem by Sir Charles Hubert Hastings Perry, if you’re interested. And it goes a little something like this, you anti-musical beast!:

]

Someone with sensitivities to these things (me) actually finds an anachronistic score quite distracting, even jarring. But maybe that’s just (me).

The most egregious example of this particular sin may be found in Kurosawa’s epic Kagemusha (1980). Like, what?, 90% of Kurosawa’s work?, it’s set in feudal Japan “in a time of increasing lawlessness”. And the score? Sounds more like “Capriccio Espagnole” meets Monty Python and the Holy Grail:

That, by the way, is the work of the Japanese composer Shin-ichirô Ikebe. Now look, it’s not like I’m saying that a Japanese film score has to be all bamboo flutes and taiko drums (not that that would necessarily be a bad thing…), and there’s no reason why a modern Japanese film composer shouldn’t avail himself of the expressive tools of Western music. I think Toru Takemitsu did a great job in another Kurosawa epic from five years later, Ran:

Yes the opening flute solo is great, but when that’s over, it’s a Western style studio orchestra. Do you hear that subtle gong action? Those upper grace notes in the melody? Just little hints of orientalism, yes, but they go a long way to making this score a very effective piece.

[p.p.s. You know who they should have gotten to write the score for The King’s Speech? Whoever it was who wrote the lush, luscious incidental music for Two Fat Ladies. Unfortunately, this particular person remains internet-anonymous, unless it was Peter Baikie who wrote the theme song. If it was he who composed and orchestrated this:

and this:

I will be suitably impressed. I will also be suitably embarrassed if someone points out that those are just excerpts from, like, a really obscure Bax piece.]