My friend Will got me hooked on the DIDA podcasts in a bad way last month, and since then I’ve listened to everyone from Artur Rubinstein to Joanna Lumley (’87 and ’07) to Kingsley Amis to Vivienne Westwood.  My favorites so far include: Gÿorgÿ Ligeti ’82, Sondheim ’80, and Imogen Holst ’72, but there is something in there for everyone.  I was surprised by how much I enjoyed Peter Maxwell Davies and Harrison Birtwistle, given what I think of their music.  Grace Bumbry‘s accent was Next Level crazy.

Because you can listen to archived episodes through the decades, you can track a (somewhat disappointing) cultural evolution.  Initially, the program was focused on classical musicians, stage actors, and poets.  Even the film stars chose all-classical selections (witness Lauren Bacall, who didn’t really seem to understand a word of what she was saying.)  Received Pronunciation was de rigeur, and Roy Plomley, the founding host, stressed the playful, imaginative side of the game.

Jimmy Stewart was one of the earliest guests I’ve found to take a mostly non-classical approach.  During Sue Lawley’s reign in the ’90s, the interviews took on a more confrontational tack, and the musical selections trended decidedly more towards pop, to the point where now, hardly anyone chooses a classical selection.  The proportion of film/TV stars and politicians invited to the show began to outweigh that of the classical artists.  People stopped disguising their regional accents.

The fun of listening to DID is, of course, concocting one’s own set of selections and responses.  Here are mine:

Questions

Could you take care of yourself on the island? Reasonably well.

Could you set up a shelter? Â Yes.

Cultivate? Sure. Â Fish? I caught an eel once.

Could you endure loneliness? Â As long as I stayed busy.

Could you rig up a shift or a raft? Â Perhaps

Would you try to escape? Â No.

Discs

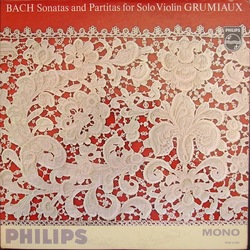

1. Bach, Complete Sonatas and Partitas for Violin, performed by Arthur Grumiaux

The profoundest and most philosophical music I know.  The fact that it is written for a solo instrument would give it a particular resonance on the island.  There are many fine recordings, but Grumiaux’s is a sentimental favorite.

2. Lyle Lovett, Pontiac

Reminds me of my childhood (my parents were both big fans) and would give me something to sing along to.

3. Beethoven, Late Quartets, performed by the Fine Arts Quartet

There’s plenty to console, perplex and mesmerize in this music. Â I would prefer the recording by the Fine Arts Quartet, but it’s not on Spotify, so the link above is for the Budapest’s recording.

4. Kurt Weill, The Seven Deadly Sins, performed by Marianne Faithfull

This is another recording that’s not on Spotify (or YouTube), but none other will do.  MF’s rendition of “The Pirate Jenny” is on the same disc, so I included it above.  More singalong fodder, beautiful orchestration and great nostalgia value.

5. Sondheim, Into the Woods, Original London Cast

Life would be hard without this.  I linked to the Original Broadway Cast under duress, since the OLC isn’t on Spotify.

6. Ravel, Daphnis et Chloé, London Symphony/Abbado

Obvs.

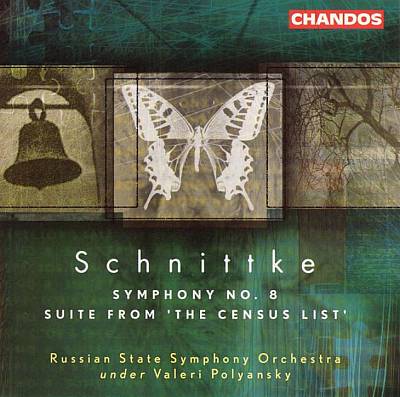

7. Schnittke, Symphony No. 8, Russian State Symphony/Polyansky

This transcendental masterpiece is paired with Schnittke’s totally irreverent score to “The Census List”. Â The two compliment each other incredibly well.

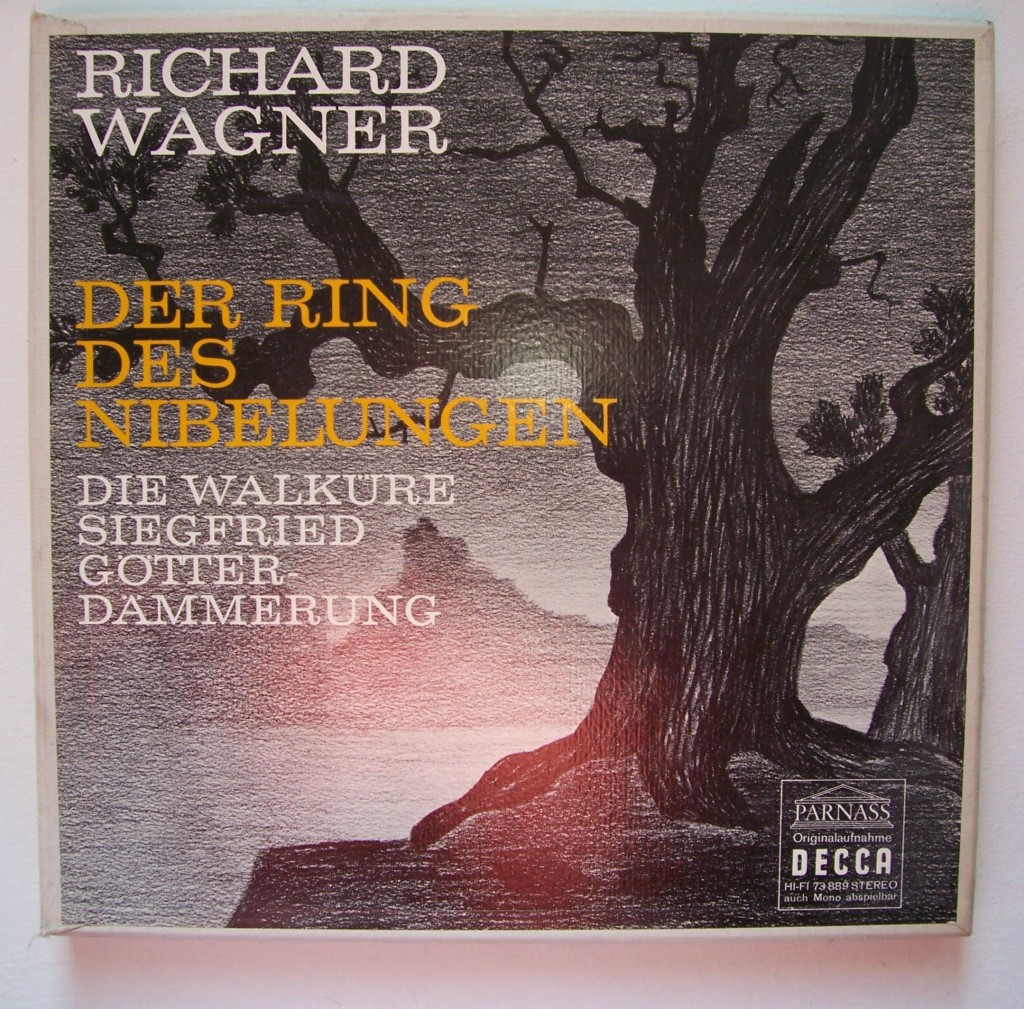

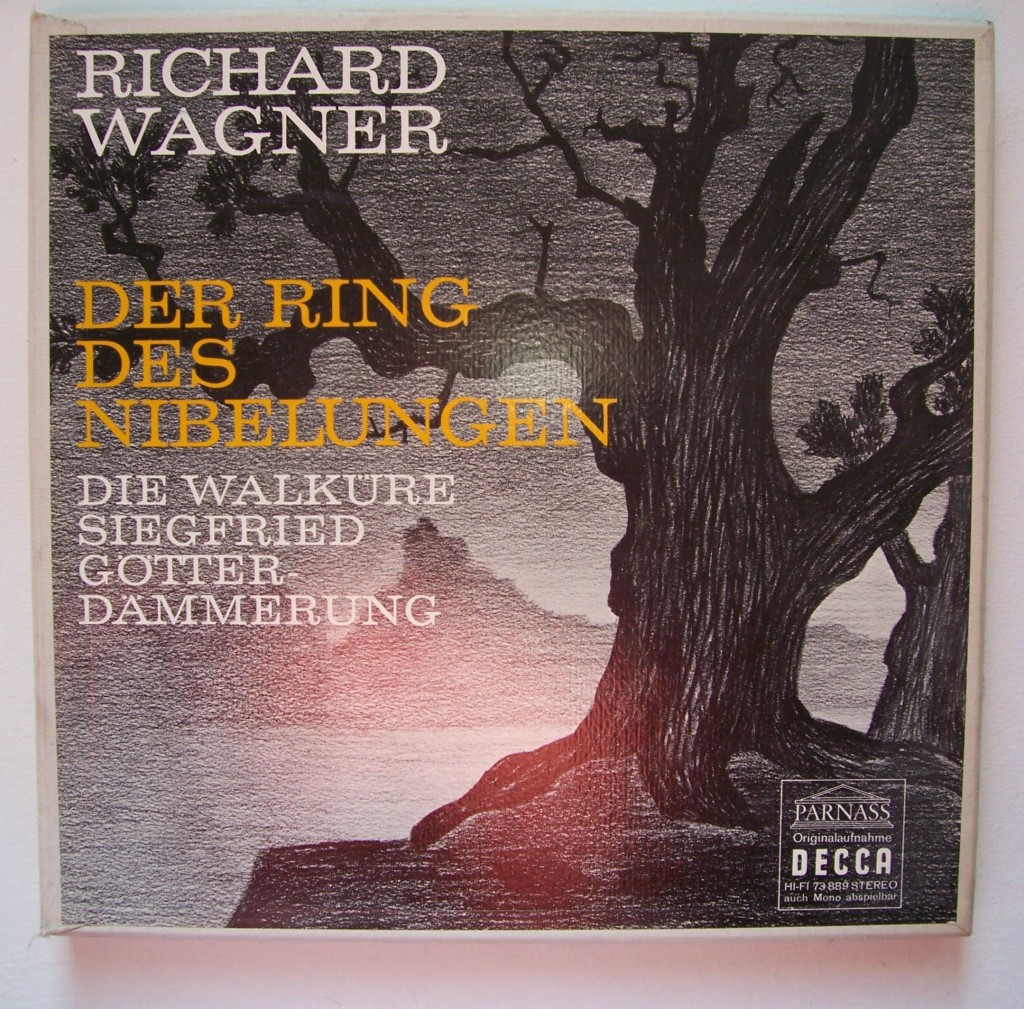

8. Wagner, Der Ring des Nibelungen, Wiener Philharmoniker/Solti

I’m not as familiar with the entirety of the Ring Cycle as I’d like to be, though my adoration of Wagner’s music increases with each passing year. Â Gaining familiarity would give me plenty to do on the island.

Book (in addition to the Bible and the complete works of Shakespeare)

If it were allowed, I’d take the Oxford Companion to Shakespeare; if not, I’d take  the entirety of A Song of Ice and Fire, as long as the 6th and 7th novels were airdropped to me when they’ve been finished.

Luxury: Piano