How copyright law promotes bad behavior in the world of classical music

This post is slightly adapted from an edition of my newsletter, Tone Prose. Subscribe for more ranting and raving!

I’ve got a concert coming up on April 6, 2024 which will feature the premiere of my new opera-oratorio Cassandra, but the program is equally exciting because it will bring me once again into collaboration with the great young pianist Joseph Vaz. Joey’s going to play Rhapsody in Blue, and having received the performance materials for this work, I’m struck by outrage, and I wish to make it known!

The publisher of Rhapsody in Blue, European-American Music, has abused its copyright privileges to offer a substandard product to interpreters of this work, and thus made the correct execution and performance of Gershwin’s music much more challenging than it should be. And while I (Will) am happy to name and shame EAM, they are simply representative of the industry-wide malfeasance. The real problem though, is the law itself.

What is Copyright?

Essentially, a copyright is a monopoly on a piece of intellectual property, such as a book, movie, recording, or, in the present case, a piece of music.

Now I don’t think you have to be the most rapacious libertarian capitalist in the world to reach the conclusion that monopolies are bad. But you don’t have to be a pinko commie tool to think that a limited monopoly granted to an artist might be good. After all, if you create an original work, shouldn’t you get some period of exclusivity in which to exploit your creation?

The first copyright law in the United States, the Copyright Act of 1790, did just that: it gave authors exclusivity on their works for a period of 14 years with an optional 14 year extension. That, I will grant, is a reasonable way of doing things. Of course, if you create a successful bit of IP, you’ll want to exploit it for as long as possible, so as corporations came on the scene and lobbyists started doing their dirty work, the original copyright provisions got distended to grossly disproportionate forms, culminating in the famous “Sonny Bono” Act of 1998. Cui bono? Sonny!

[A brief aside: don’t let Sonny Bono’s cameo on The Golden Girls fool you — he was one bad hombre. Aside from his rotten-to-the-core copyright extension act designed to protect Disney’s copyright on Mickey Mouse, he was also a raging NIMBY exclusionist zoning champion as mayor of Palm Springs, and gave Newt Gingrich PR advice.]

The Baroque State of U.S. Copyright Law

In the US, we are currently operating under a dual copyright regime:

- For works created prior to 1978, the maximum copyright duration is 95 years from the date of publication, or 120 years from the date of creation, whichever is shorter.

- For works created in or after 1978, the maximum copyright duration is “life of the author” + 70 years.

As to the question of Rhapsody in Blue, attentive readers of Listener Laurie’s comment will have noted that 2024 is the centennial of this great masterpiece of symphonic jazz. So, you might ask yourself, shouldn’t the music be in the public domain? Can’t you just download the parts from the Internet Music Score Library Project? Why does a publisher have to be involved at all?

Enter Ferde Grofé

First thing first: the original score of Rhapsody in Blue *is* in the public domain, and you *can* download it from imslp. The problem is, the original version of Rhapsody in Blue isn’t the version that anyone actually plays.

Well, it’s not *no one* who plays it — in fact, there’s a very cool recording of the original version, scored for Paul Whiteman’s dance band in 1924, performed by George Gershwin himself on a piano roll, with MTT conducting. (The tempi are nuts.) But Gershwin didn’t *orchestrate* the Rhapsody. That job was left to American composer Ferde Grofé (of “On the Trail” fame). Grofé revised and expanded this version in 1926, but it wasn’t until 1942 that he scored it for a normally-constituted symphony orchestra, and that’s now the version that “everyone” plays.

Material Interests

This 1942 version of Rhapsody in Blue remains under copyright until 2038. Which means that the publisher, European-American Music, retains a monopoly on the performing materials for another 14 years.

As we all know, the problem with a monopoly is that the monopolizer has no incentive to provide their customer with a decent product or service, and that’s exactly the problem here. First off, I placed Harmonia’s rental order for these materials back in May of 2023. I signed a contract that stated exactly when the sheet music was to arrive. That date came and went, and when I contacted EAM, it turned out they had lost track of the order.

Then things got worse: EAM sent me a freshly printed set of parts. These parts were engraved in 1942 using 1942 technology and 1942 Broadway notational conventions. When you first glance at the music on the page, it doesn’t look too shabby. But take a closer look:

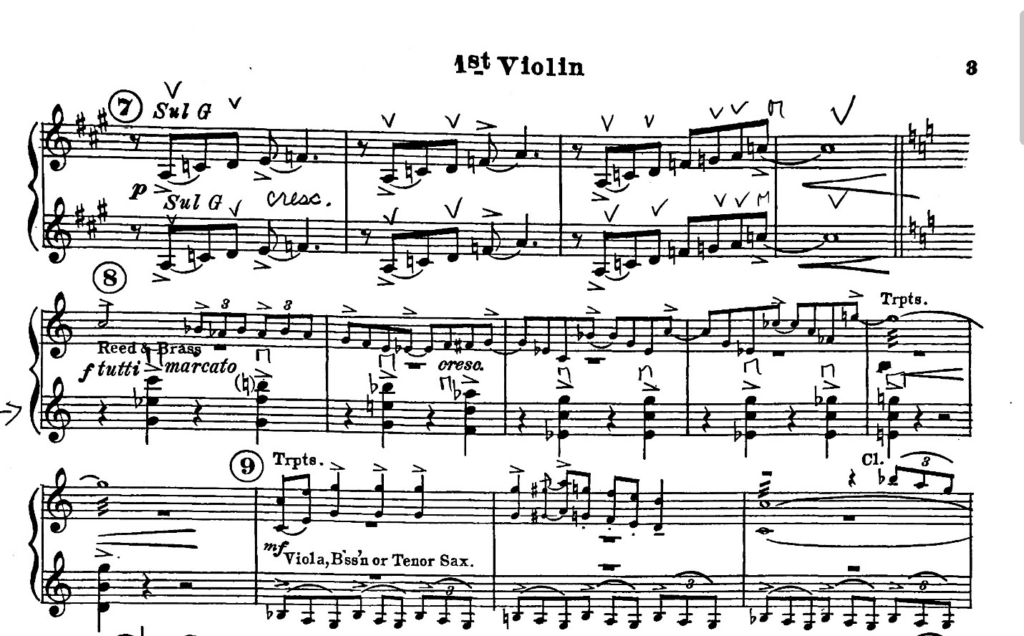

Notice, for example, that after the first line of music, the clef is never re-printed, and neither is the key signature. That’s very poor indeed. The problems don’t stop there though: these parts were written so that the piece could be performed with any hackneyed, ill-constituted civic band, and so the parts are laden with cues to such an extent that they are almost impossible to read. This tendency reaches its ne plus ultra in the first violin part, which is clearly designed as a quasi conductor’s score for concertmasters who are also the leaders of their bands.

Errata

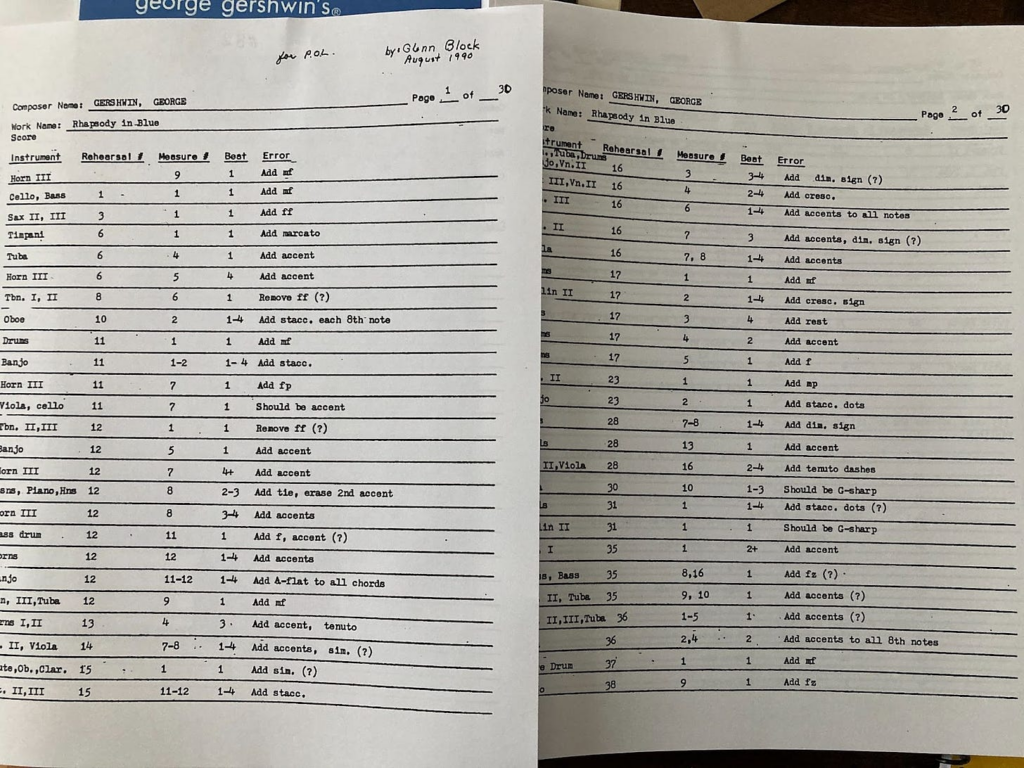

And now for the pièce de résistance: EAM doesn’t just sent the parts, they also send a printout of the 30-page errata list of corrections that need to be marked into all the parts.

Just think about this for a second: the parts were engraved in 1942. This errata list was compiled in 1990. That means that the publisher has had 34 years during which they could have re-engraved the piece so as to incorporate all these corrections.

But why would they? That might cost… oh a few thousand bucks I guess? It’s so much easier to make the renters of this material do the work themselves (as I did.) Who are the renters going to complain to? What competitor are they going to turn to? There is none — that’s the whole point of a monopoly!

Bad Actors, Bad Incentives

This whole thing reminds me of the problem with drivers.

Bad drivers should certainly be held to account for speeding and running stop signs. It’s antisocial behavior that can easily get people hurt or killed. But the real criminals are the transportation engineers and urban planners who have designed the road infrastructure that encourages speeding. The real criminals are the lobbyists who have been working on behalf of the auto manufacturers for a century to ensure that America is designed for car dependence. The real criminals are the lawmakers and politicians who have created a permissive legal structure where killing someone with a private automobile isn’t even considered a case of criminal conduct.

Preaching, Practicing

I’d be a fool if I didn’t mention that I, as a publisher of my own music, try to do everything that EAM doesn’t. First off, for the most part, I sell rather than rent. People can buy my music directly from this web site, print out their own copies (in whatever numbers they like) and perform it to their heart’s content. I also try very hard to make sure that the editions offered on this site are free from mistakes (though I am convinced it is a metaphysical impossibility to get them all.)