Dramatic Cantata for Baritone, Chorus, and Orchestra

2.2.3.2 – 4.3.3.1 – tmp+3 – hpschd, pno, org – str; B solo, SATB chorus

Staging

The off-stage brass should be positioned along the sides of the hall, with one horn, trumpet, and trombone on each side. The trombones should be furthest back (away from the stage), the horns in the middle, and the trumpets furthest forward (close to the stage.)

The processional drummer precedes The Judge in the procession.

Two non-speaking / non-singing extras (The Judge’s attendants) should follow.

The Judge is followed by a spotlight during the procession.

The Judge wears a cloak and mask during the procession; underneath, he wears a business suit. The attendants wear robes or shrouds, the drummer wears something similar.

Props required: The Judge’s throne, crown, large antique book, attendants’ scrolls and quills (1 each), reading glasses, prie-dieu.

Program Note

Dies Irae is the third major choral-orchestral work I have composed for Harmonia. The first, The Muses (2022), had as its subject the mystery of artistic inspiration. The second, Cassandra (2024), was about speaking truth to power. The subject of Dies Irae is righteous indignation (and its constant bedfellow, rank hypocrisy).

The Text

The “Dies Irae” is a Latin poem that likely dates from the middle of the 13th century AD. The identity of the poet is lost to the ages, but there is a good chance it was written by Latino Malabranca, a Roman noble and clergyman whose uncle was elevated to the papacy. Malabranca himself attained an exceptionally high rank in the Catholic hierarchy, being named head of the Papal Inquisition in 1278. This was the period during which the Inquisition was at its most zealous, with the church council frequently turning over heretics to local authorities for all manner of medieval punishment. It’s this association that makes me suspect Malabranca as the likeliest of the poem’s authorial candidates, given its themes of revenge and retribution.

In its original form, the poem featured 18 verses of three lines each. At some point in the centuries that followed its initial composition, the final verse was modified, breaking the verse pattern and scansion. What we have now is a poem of 20 verses in which the first 17 flow with a highly regular (and disturbingly sing-song) lilt, and the final three constitute a disjointed appendix.

The poem’s content is, in effect, a gloss on the Book of Revelation: the final, controversial book of the New Testament. The poem distills Revelation’s dark vision of the Day of Judgment, when the Judge of Righteousness (presumably God the Father, but perhaps Jesus) will descend to Earth to separate the wicked from the blessed. In just a few short lines, the poem presents all of the most powerful images associated with this event: the summoning of the dead from their graves, the blast of the trumpet, the heavenly Judge reading his verdicts from “the book in which all is contained,” and the eternal hellfire waiting for those who don’t pass muster.

The Requiem

The next step in this poem’s history is one that I will admit I find altogether perplexing. At some point in the ≈150 years that followed, the poem was subsumed into the Requiem Mass and became a formal part of the Roman Catholic liturgy for the dead. I can only imagine the first time that a (literal) Goth edgelord stood up to read a poem at his dad’s funeral and launched in with, “The day of wrath, that day will dissolve the world in ashes… .” I wish there could have been an Office-style mockumentary to capture the wide-eyed side glances between the other parishioners.

However it happened, the poem became part of the liturgy, and it is in this form that the words have become so well known today. Many great composers have set these words to music as part of their music for the complete Requiem Mass. Mozart’s and Verdi’s settings have even achieved escape velocity and become well known outside the confines of classical music.

The Melody

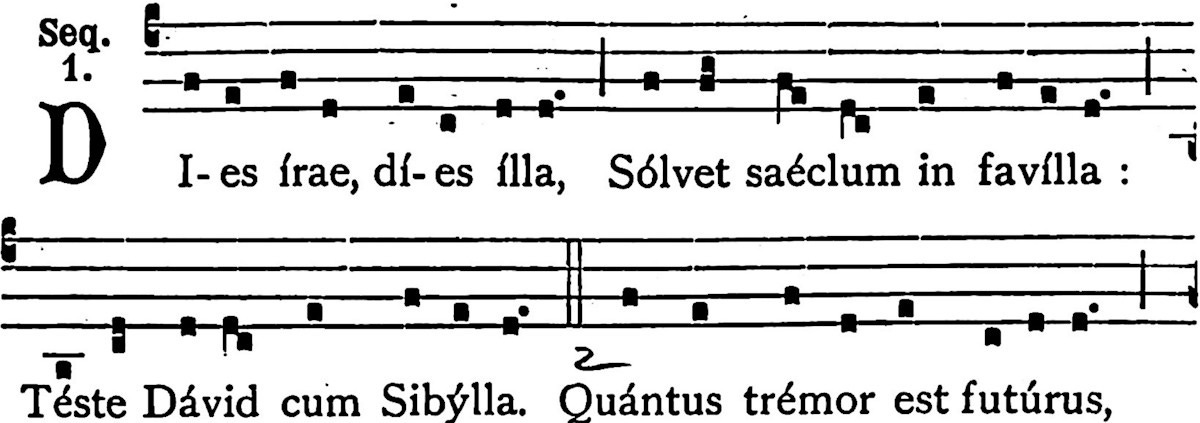

The music of Mozart and Verdi should not, however, be confused with the original musical setting of the words of the “Dies Irae.” The poem was first set to music very early on, probably before the year 1300, as a Gregorian chant:

The tune has gone on to have a life of its own, especially the first eight-note motive, and most especially the first four notes. This little melodic riff has become a musical shorthand for all things related to death and the macabre. It has been quoted — just the notes mind you, not the words — by everyone from Berlioz to Chopin to Brahms to Liszt to Mahler to Shostakovich to Ligeti to Wendy Carlos to Stephen Sondheim. The composer who got the most mileage out of it has got to have been Sergei Rachmaninov, who was obsessed with death and wanted everyone to know it.

The plainchant setting of the “Dies Irae” is, however, not limited to the first eight notes: all 20 lines of the poem are set to music in a rather complicated melodic structure that (bear with me) goes aabbcc aabbcc aabbcdef. The b section (not to mention the c, d, e or f sections) is hardly ever referenced in music by other composers.

Beyond The Requiem

Given the fact that the “Dies Irae” was written as a standalone poem, I find it surprising that it has only rarely been set to music outside the context of the Requiem Mass. In fact, the only instance I know of a composer using the text in this way comes from Jean-Baptiste Lully in 1683.]

I was inspired to set the text while preparing for Harmonia’s performance of the Mozart Requiem in November of 2022. It wasn’t until then that I learned about the history of the “Dies Irae,” and when I found out that it began life as an independent text, it just seemed like the most obvious thing in the world to set it as a standalone composition.

That was all well and good, but then I had a decision to make: whether to set the words to my own original music or to use the pre-existing Gregorian chant melody. And if I did use the chant, would I use the whole thing, or just make occasional allusions to the “head motive” during the piece?

I decided to go for broke. In this piece — with precious few exceptions — the entire chant melody is presented intact, tethered to its original words. As far as I can tell, this hasn’t been attempted since a Requiem setting of Antoine Brumel in 1500, but I can assure you, it has led to exceedingly different results.

The Judge

Not surprisingly for a poem about the day of judgement, the “Dies Irae” makes frequent reference to “Judex,” that is, “The Judge,” but this judge never enters the scene as a “character” per se. That hole at the center of the text makes one wonder, if the judge did show up, what would he say?

This became a pressing issue for me, because early on in my conceptualization of this piece, I decided to include a part for solo baritone, and not just for any solo baritone, but specifically for Zachary Lenox. I had been wanting to write something substantial for Mr. Lenox since he began appearing as a soloist with Harmonia four years ago. I have rarely encountered a bass-baritone (which I’m convinced he really is) who is able to wield such grandeur of sound with such virtuosity of technique.

But I had to decide if the soloist would sing bits of the actual “Dies Irae” text or something else. This resulted in a wild-goose chase, from court verdicts throughout history (including in the Inquisition) to ancient documents concerning justice, and I even considered commissioning a contemporary poet to create something new.

Then on one fateful night, an hours-long session of multi-lingual Googling led me to the perfect text: the anonymous libretto of an obscure Latin cantata by Marc-Antoîne Charpentier titled Extremum Dei Judicium.

Extremum Dei Judicium

Very little information survives about Extremum Dei Judicium (“God’s Last Judgment”). As far as anyone can tell, it was composed in Paris in the 1690s. Charpentier, a middle-Baroque French composer best known for his Messe de minuit (“Midnight Mass for Christmas”) had studied in Rome during the 1660s with Giacomo Carissimi, the Italian composer who basically invented the genre of the Latin oratorio (exemplified by his Jephthe, a favorite of some extremely peculiar people).

Extremum Dei Judicium is exactly what I was after, basically a rendering of the “Dies Irae” into a dramatic scene. (Charpentier referred to his works this genre as “histoires sacrées.”) There are roles for angels, a chorus of the damned, a chorus of the blessed, and — most crucially — God.

It took me ages to track down a source for the actual text of this oratorio, but I was able to find a scan of a handwritten vocal part created for a performance in France in the 1970s. As I started reading the first “Récit de Dieu,” my internal alarm bells began ringing. I typed out the text as quickly as I could so that I could check Google Translate against my barely adequate literacy in Latin.

“Hear, O heavens, what I say, let the Earth hear the words of my mouth. I have looked down from on high upon the children of men to see if there is any that understandeth or seeketh after God: and there is none that doeth good, not one. Wicked and perverse generation, dost thou render this unto thy Lord? Foolish and unwise people, dost thou render this unto thy God?”

Now that’s what I’m talking about!

The Orchestra

I have scored this work for a rather eccentric instrumentarium. First and foremost are three keyboards: piano, organ and harpsichord, a trio highly favored by the Alfred Schnittke, who was, is, and shall remain one of my primary musical inspirations. (I will freely admit that, in many ways, this piece is my version of Schnittke’s Faust Cantata.)

The woodwind section is also unusual, in that there is one of each instrument, but not just one flute, one oboe, etc. I invited all the siblings along, so there’s piccolo, English horn, clarinets in three sizes, and contrabassoon.

The brass section is normal, except that the players are dispersed around the hall in such a way as to make for dramatic effect (which I will not spoil here). The percussion section includes several toys, such as the flexatone, along with certain left-field instruments, such as the daluo (a Chinese ascending-pitch hand gong.)

The Form

The piece is through-composed, but there are definite “movements” within this form: the first six verses of the “Dies Irae” comprise the opening section, followed by an arioso and rage aria for the Judge (in the mode of a manic, bluesy lounge-lizard song).

This is followed by a “slow movement” for the chorus once again, singing the seventh through twelfth verses of the poem. Then we get another arioso for the Judge, followed by a pair of songs for his character in which the chorus also sings. The first of these is the only extended portion of the piece set in the major mode; the second is a “broken mirror” reflection of the first (naturally, in minor), in which I imagined what it would sound like if Elvis were to sing a Verdi aria. In Latin.

The work concludes with a slow-building coda, an unholy benediction, and a final amen.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.