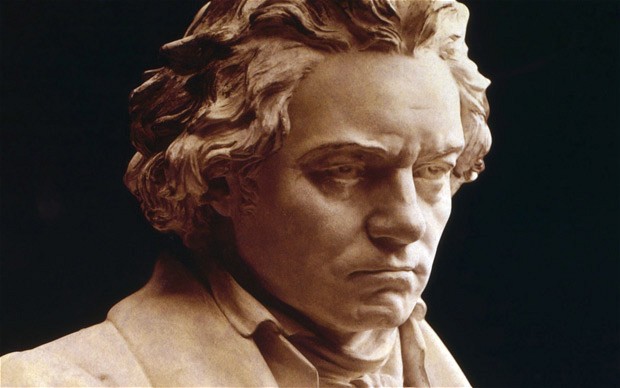

I’ve been thinking about two majorly large works over the past few weeks, Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis and 9th Symphony, gargantutrons which naturally lend themselves to wide-ranging analyses of their composer’s thoughts and philosophy. But at the same time, I myself was composing what is undeniably a minor work, a short anthem for four-part choir with piano, written for a church choir of about a dozen volunteer singers. I’m as prone to dreams of grandiosity as any other composer, but composing a little thing like this is undeniably fun, and it’s got me thinking that we too often overlook the little gems from composers far greater than myself.

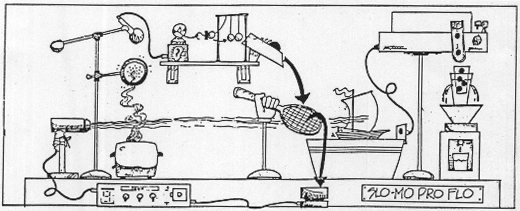

Composing anything, be it a piece of music, a work of fiction, a painting on canvass, is really all about setting up a set of rules and then playing by them (or not). Every piece is a game. For example, in this little anthem I just finished the guidelines were: the text (chosen by the church), the number of voice parts (4), the ranges of the singers (amateur-level), the rehearsal time (not much), and the pianist’s capability (virtuosic). So right off the bat, there’s a balancing between a relatively simple choral part against a freewheeling piano part. With only four voice parts in the choir, every chord has to be voiced just so, or the ear will immediately catch the problem. The architecture of the piece has to be planned very carefully, since melodic highs can’t really be all that high. Not to mention, the text has to be understandable, and, ideally, expressively musicalized.

But now back to Beethoven, and these two enormous pieces which took him a combined 6 years to compose (or, really, a lifetime if you consider that in the ninth, he used melodies sketched as early as the 1790’s.) The 9th symphony is probably the single most effective piece ever written for a large concert hall with a huge audience. Listening to the “Ode to Joy”, that great paen to human brotherhood, it’s impossible not to to feel like everyone listening in the hall with you is your sibling.

But here’s a little something for you: did you know that Schiller’s poem “An die Freude” had already been set to music numerous times before Beethoven got around to it, including by one Franz Schubert?

Schiller’s poem was an example of the geselliges Lied (social song), a poem the author expected to be set to music and sung by groups of friends with glasses in hand. And you’ve got to admit, Schubert’s setting captures that blustery spirit in a way that Beethoven’s lofty, grandiose music doesn’t quite. Beethoven left out some lines such as

Freude trinken alle Wesen

An den Brüsten der Natur,

Alle Guten, all Bösen,

Folgen ihrer Rosenspur

(Joy all creatures drink at the breast of Nature, All that’s good, all that’s dumb, follow her rose-petaled path) – lines that look a lot better through rosy-petaled beer goggles at the pub.

Composers often use a smaller works the breeding grounds for larger ones, but it’s a mistake to view them as just so many little experiments. Just as often, a composer may have been working on something big, and found that a certain piece of material, though charming of its own accord, just didn’t fit right in context. Sometimes these musical cuttings can find their rightful home replanted in a little ditty somewhere down the line. Just because a melody is used in a song instead of a symphony doesn’t make it any less beautiful.